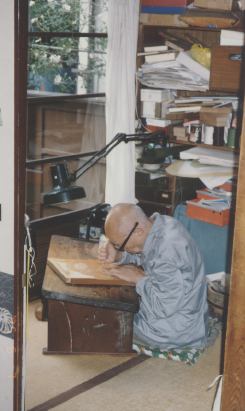

Mr. Susumu Ito, carver

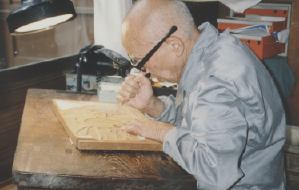

It is the bench that immediately captures my attention as we step into the room. It is wide and low, made from hard, heavy keyaki wood, battered and scarred from decades of daily use, with the top surface deeply burnished by rubbing from the cloth that protects the back surface of the woodblocks. It stands in front of the window overlooking the garden, and the diffused light from today's over-cast sky falls softly over the half finished wood-block resting on its surface, throwing the carved lines into clear relief.

A carving knife, the wood of the handle

also polished by long use until it glows, lies on the bench next to

the block where the carver has put it down to turn and greet us. The

workbench, the woodblock, the knife ... they make up a picture the

details of which have not changed in more than a hundred years, in

far more than a hundred years. My friend Sadako and I have come to

see this picture, and to hear some of the story to be told by Mr.

Susumu Ito, master woodblock carver, working here at his home tucked

away in the narrow back streets of Arakawa-ku, in Tokyo's shitamachi

district.

A carving knife, the wood of the handle

also polished by long use until it glows, lies on the bench next to

the block where the carver has put it down to turn and greet us. The

workbench, the woodblock, the knife ... they make up a picture the

details of which have not changed in more than a hundred years, in

far more than a hundred years. My friend Sadako and I have come to

see this picture, and to hear some of the story to be told by Mr.

Susumu Ito, master woodblock carver, working here at his home tucked

away in the narrow back streets of Arakawa-ku, in Tokyo's shitamachi

district.

He has been living and working there in this house, here in this tiny 2-mat room, for more decades than I have been alive ... many more. For most of his 80-odd years, ever since first picking up the carving tools at age 12, he has sat in front of such a workbench, gripping the delicate knife in his right hand, almost burying it in his grip, and carving, carving, carving ... How many blocks have passed over the surface of this bench? How many prints has he made? It has never occured to him to try and answer that question. For Ito-san, this is simply his job, his daily work.

Before leaving my home today to come to this place, I had spent some time studying a particular print I own, a reproduction of a famous Utamaro design. Had studied the delicate, almost invisible hair lines surrounding the face of the woman depicted, the flowing curves of the lines of the fabrics, the smooth sharp lines of the fan she is holding ... all these lines carved by Ito-san at this very bench some years ago. Carved with supreme confidence, and with a skill which I sometimes despair of ever reaching.

When, during our visit, I show Ito-san some of my own prints, and one of my carved blocks, I suddenly find that now, as I sit here next to him in this room, the work that I had thought was actually 'not too bad', somehow has come to look clumsy and amateurish. He looks them over - for quite a long time - and makes some very kind comments, but I have to wonder what he really thinks of all this; of this foreigner who is trying to follow such a path.

During our conversation, he uses a number of times the expression 'shumi', hobby, when talking about my work, but he is not doing so in a patronizing way. Rather, he is trying to express the idea that unlike him, I am free to truly enjoy the work that I am doing, by choosing what to carve, how to print it, where to sell it, etc. etc. For Ito-san, on the other hand, the word that must be used is 'shigoto', work. It is not for him to ask those questions, but simply to accept whatever jobs come from the publishers. He has carved and re-carved the same popular Hiroshige or Hokusai prints many times over, and yet he would not think to complain about the repetition. He is a carver ... and it is his job to carve ... For myself, I could not conceive of doing the same print again and again. But I am not really a 'shokunin'. Even though I make a living at this work, I am still a kind of an 'amateur' at this; an amateur in the original French sense of the word - one who 'loves' ...

But I am sure that Ito-san too, loves

his work. He doesn't 'think' about it anywhere near as much as I do,

and on a number of occasions during our conversation, he had to pause

and think twice before responding to something I had asked, as he had

never before considered such matters. Woodcarving is not an

intellectual pursuit for him, but simply a way of life. He eats,

breathes ... and carves.

But I am sure that Ito-san too, loves

his work. He doesn't 'think' about it anywhere near as much as I do,

and on a number of occasions during our conversation, he had to pause

and think twice before responding to something I had asked, as he had

never before considered such matters. Woodcarving is not an

intellectual pursuit for him, but simply a way of life. He eats,

breathes ... and carves.

Ito-san told us that when he started in this craft, there were upwards of 250 men making a living carving blocks, but thought that there were perhaps now only about ten or so. Whether or not this number will decrease even further, or remain stable, seemed to bother him not at all. This quiet, contented man does not seem overly concerned with the doings of the world outside his window. His world is here in this tiny room, in the drawers full of tools, and in the woodblock waiting on the bench ... I am sure that not two minutes after we had departed, taking our 'noisy' questions with us, he was back sitting on his zabuton, his nose not 10 centimeters from the surface of the wood, his entire concentration focused on the knife slicing its way through the hard cherry wood. He is a carver ... and it is his job to carve ...

I am only half Ito-san's age, and have been carving less than a quarter of the number of years that he has worked. Even though I sometimes feel pride about my developing skills, a visit such as today's makes me realize that I am still very much a beginner. Many more years will have to pass by before I can honestly call myself a carver. When I am in my 80's, will I still be sitting at a bench such as this, holding a knife like this, carving smooth lines like this? I cannot answer such a question. It is impossible for me to create such a picture in my mind. I am still too young. But of one thing I am sure - that of all the possible futures that lie in front of me, I can think of very few that seem so satisfying as this one ...

Ito-san, congratulations on making such a happy productive life for yourself. May your coming years be full of peaceful contentment thinking over the time so well spent ...

This particular move turned out to have a major

impact on my life. When I went to the local high school to register

for classes, I had a meeting with one of the teachers to try and

decide what courses to take (the school year had already been under

way for a couple of months). After filling in the courses required

for my particular 'stream' (potential university entrance), there was

one blank slot left. The teacher noticed on my papers that my father

was a musician. "Why don't you take band class? Do you play an

instrument?"

This particular move turned out to have a major

impact on my life. When I went to the local high school to register

for classes, I had a meeting with one of the teachers to try and

decide what courses to take (the school year had already been under

way for a couple of months). After filling in the courses required

for my particular 'stream' (potential university entrance), there was

one blank slot left. The teacher noticed on my papers that my father

was a musician. "Why don't you take band class? Do you play an

instrument?"

On the occasions when I have

sat in the rooms above his workshop and talked with him and his wife

Chieko-san, I have sometimes felt like I was talking to one of the

craftsmen in my own field ... Just the very day before visiting to

take the photos for this story for example, I had visited Ito-san the

carver (whose story starts on the next page), and the pages of

jottings from that visit in my notebook might have been written about

Tsuburaya-san, so much is similar. The description of younger days

learning the craft from a strict master ... "He wouldn't tell me

anything! ..."; of long, long days of hard work ...; of seeing the

world change and demand for his products decrease ... Tatami and

hanga may be two very different products, but the craftsman's world

is much the same ...

On the occasions when I have

sat in the rooms above his workshop and talked with him and his wife

Chieko-san, I have sometimes felt like I was talking to one of the

craftsmen in my own field ... Just the very day before visiting to

take the photos for this story for example, I had visited Ito-san the

carver (whose story starts on the next page), and the pages of

jottings from that visit in my notebook might have been written about

Tsuburaya-san, so much is similar. The description of younger days

learning the craft from a strict master ... "He wouldn't tell me

anything! ..."; of long, long days of hard work ...; of seeing the

world change and demand for his products decrease ... Tatami and

hanga may be two very different products, but the craftsman's world

is much the same ...

In the Autumn issue of 'Hyaku-nin Issho' last

year, I mentioned that I had been doing some writing for the

'Mainichi Weekly' newspaper, having been asked to contribute short

essays for their front page. I've been having fun doing that, and

this spring, got a chance to do more for them. They asked me if I

would be interested in doing a weekly column, and of course I

accepted immediately.

In the Autumn issue of 'Hyaku-nin Issho' last

year, I mentioned that I had been doing some writing for the

'Mainichi Weekly' newspaper, having been asked to contribute short

essays for their front page. I've been having fun doing that, and

this spring, got a chance to do more for them. They asked me if I

would be interested in doing a weekly column, and of course I

accepted immediately.