Forgotten Beauty of Woodblock Prints

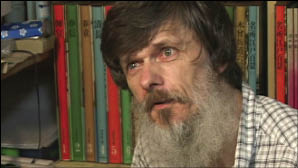

A few months from now, sometime early in the new year, I will reach the 20th anniversary of becoming a professional printmaker, as it was in early 1989 that my project to create the 100 prints of the Hyakunin Isshu poets began. Since that time, I have been interviewed by the media more times than I can possibly count - for newspapers, magazines, radio and television. This publicity has of course helped me expose my work, but reading 200 newspaper stories about this man does of course not give you 200 times as much information - you simply read pretty much the same thing 200 times!

So although I usually accede to media requests, and do my best to be a 'good' interviewee, when seen from my point of view, the resulting stories or programs are invariably simplified and shallow, giving nothing more than the barest outline of what I am doing.

So although I usually accede to media requests, and do my best to be a 'good' interviewee, when seen from my point of view, the resulting stories or programs are invariably simplified and shallow, giving nothing more than the barest outline of what I am doing.

I had a good chance once - as the subject of an hour-long television documentary - to correct this imbalance, and that program did indeed show much more depth to my work, but I was inexperienced at dealing with the media, and the producers created a somewhat melodramatic view of my life based on what they felt television viewers wanted to see.

How then, can I redress this situation? Opportunities for hour-long documentaries are of course very few and far between; I can't expect to be in that situation again any time soon. It occurs to me though, that I don't need the cameras; why not sit down and write what I would like to be shown on such a program? After all, I myself understand my work far better than any producer.

So let's use this idea as the seed for a new series of stories in this Hyakunin Issho newsletter; I will try to create a scenario for an hour-long program on my printmaking activities. A program that - I hope - will cover the things that I myself think are most relevant, and important.

Let's see ... an hour-long program would perhaps have six sections of about eight or nine minutes, divided by commercials. I think the best place to begin is down in my workroom. It's actually cloudy and chilly as I sit here writing this, but a scriptwriter has great freedom ... Let's make it a beautiful warm and sunny day ...

Lights ... camera ... action!

***

[Part One]

[Cold Open] [Camera] Rippling water flowing past mossy stones. We hear the gentle sound of the stream, as well as birdsong. Slowly, the camera pulls back and pans along the scene - a small river surrounded by greenery. As we pull back further, we realize that the camera is shooting out a window. The interior of the room begins to become visible, and as it does, the sounds change; the ripple of the river fades, and a new sound becomes audible - the faint sound of a sharp blade cutting through wood. We are in David's workshop, and he is carving. We watch.

[Cold Open] [Camera] Rippling water flowing past mossy stones. We hear the gentle sound of the stream, as well as birdsong. Slowly, the camera pulls back and pans along the scene - a small river surrounded by greenery. As we pull back further, we realize that the camera is shooting out a window. The interior of the room begins to become visible, and as it does, the sounds change; the ripple of the river fades, and a new sound becomes audible - the faint sound of a sharp blade cutting through wood. We are in David's workshop, and he is carving. We watch.

[Narration] Ome. Tokyo. The river-side workroom of woodblock printmaker David Bull. You can hear - if you listen carefully - the sound of David's blade moving through the wood. The steel of his cutting knife is laminated with the same technology used for making Japanese swords; the wood is the hard and dense yamazakura - the mountain cherry - for centuries the choice of material for making Japanese prints. [... the sound of the cutting ...]

[David (voice over)] "I can hear - as well as feel - when the blade needs sharpening; the knife starts to tear its way through the wood instead of slicing. It is vitally important to keep it as sharp as possible. Many of the carved lines in my prints are extremely fine; if the knife is too dull, the edge of the wood becomes slightly torn, allowing water to enter during the printing stage. The printed lines lose their delicate character ..."

[David (voice over)] "I can hear - as well as feel - when the blade needs sharpening; the knife starts to tear its way through the wood instead of slicing. It is vitally important to keep it as sharp as possible. Many of the carved lines in my prints are extremely fine; if the knife is too dull, the edge of the wood becomes slightly torn, allowing water to enter during the printing stage. The printed lines lose their delicate character ..."

[Camera] Closeups and pans over some of David's prints (classical reproductions). As we view the images in measured detail, David speaks.

[David (voice over)] "The traditional woodblock prints of Japan represent one of the most astonishing achievements in world art. Those who study the arts of different cultures recognize a number of major 'peaks' of human accomplishment: the marbles of ancient Greece, the paintings of the Italian Renaissance, the symphonies of the German tradition ... It is clear to us now that the body of work created by the print designers and craftsmen of Edo is also one of the supreme achievements of mankind, although none of the men who took part in the creation of the prints ever had the faintest idea that their work could be measured in that way.

"We are all familiar with the story of how the prints became known - how the Europeans who first saw them were astonished by the - to them - completely 'new' way of making images. The flat colour, the marvellous use of empty space ... the sensuous calligraphic line ... all these things had a major impact on art and design in other cultures.

[David (to the camera)] "This was followed, over a period of many years, by an increased appreciation of Japanese prints in their home country. The typical Japanese person these days feels that they have a basic understanding of these prints. Everybody knows the big names: the Hokusai, Hiroshige, Sharaku and Utamaro. Everybody has seen the most iconic images: the great wave, the old Tokaido, the grimacing kabuki actor, and the courtesan in the Yoshiwara. Daily we see these images reproduced everywhere.

"But if those images are all that come to mind when the words 'traditional woodblock printmaking' are spoken, then you have missed a great deal. Just as is the case with 'Famous Places', either here in Japan or overseas, in our eagerness to experience the 'best', we ignore everything else. And as the 'best' has become plasticized and touristified and altered beyond recognition, we end up seeing, and experiencing, and understanding ... nothing.

"There is a simple question that I ask of all visitors to my workroom, "Have you ever seen a Japanese print?" They always answer "Yes". And always, a short time later - after an enjoyable session of chatting and viewing prints in my room - they all say the same thing, "Now I see. I had no idea ..."

"They had no idea. They, and nearly everybody else living on these islands, had forgotten. In their worship of the Great Wave, they have forgotten ..."

[Main Title]

The Forgotten Beauty of Japanese Woodblock Prints

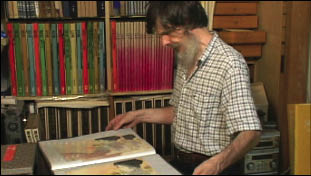

[Camera: as titles roll ...] Back at the carving scene in the workshop. David seems to come to the end of a particular section of the work; he puts down his tool, straightens things up a bit, and gets up from the bench. Cut to outside: view of the river, but at one side of the screen, David comes out of the workshop door, and heads upstairs. Cut to room upstairs: Dave comes in, goes to the print storage shelves, pulls a folder out, sits down, and shows it to us ...

[Camera: as titles roll ...] Back at the carving scene in the workshop. David seems to come to the end of a particular section of the work; he puts down his tool, straightens things up a bit, and gets up from the bench. Cut to outside: view of the river, but at one side of the screen, David comes out of the workshop door, and heads upstairs. Cut to room upstairs: Dave comes in, goes to the print storage shelves, pulls a folder out, sits down, and shows it to us ...

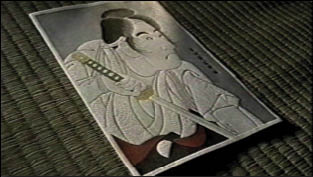

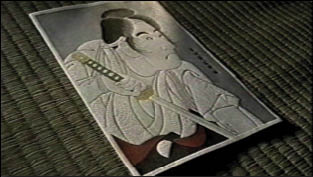

[David] "I've prepared a little test for you. I hope you don't mind. Let me hold this piece of paper so that you can see it. Now, what do you think? Is this a woodblock print, or is this a colour copy?"

[Narrator] David asks many of his visitors this same question. We lean closer to look at the image, but it is not easy to answer his question. It looks like a typical Japanese print, but is he trying to trick us, with a colour copy he has made? We can't tell ...

[David] "Please don't feel embarrassed ... I'm not actually trying to trick you. Perhaps if I change the light, you may be able to answer with more confidence."

[Camera] David stands up and turns off the overhead light. He then places the sheet on a low table near the window. We look closely. It has changed dramatically; under this light, we can see clearly that it is a woodblock print. Zoom in as David gestures to parts of the image as he speaks ...

[David] "Now there is no doubt, is there? This is a woodblock print! Look at it! You can see - even feel - the lovely texture of the washi. Over here there is a place where the printed lines are embossed into the body of the paper. Look there, where these colours blend together so beautifully ... And everywhere - the pigment has been taken up between the fibres of the washi; it's an exquisite sensation to see this!

[David] "Now there is no doubt, is there? This is a woodblock print! Look at it! You can see - even feel - the lovely texture of the washi. Over here there is a place where the printed lines are embossed into the body of the paper. Look there, where these colours blend together so beautifully ... And everywhere - the pigment has been taken up between the fibres of the washi; it's an exquisite sensation to see this!

"What caused this transformation? It was the fact that we are now looking at the print in the same sort of environment in which it was created - in a horizontal position, under soft horizontal light!

"Think about a bit of history; back in the old days - Edo ... Meiji ... - there was no illumination coming from the ceiling of each room. The light came from windows, or - in the evening - lamps. This is hugely important; the light falls horizontally onto the print."

[Camera] David 'acts out' these next points he makes.

[David] "But it's not just the direction of the light. Think about how images are created - in the west, and in the east. The men who designed Japanese prints did so by placing sheets of paper on a low table, or directly onto the tatami, and then drawing on them. The paper was, again, in a horizontal position. Compare that with what happens in the west - the canvas is on an easel, in a vertical position. So of course the whole concepts of perspective and proportion are completely different. The western picture is painted on an easel, and then viewed in a frame on a wall, as though we were looking through a window at the scene. It works well.

"But the Japanese images were created in a horizontal orientation, with that mindset, and now we put them in frames and hang them on walls! This is crazy!

"There is yet more! You know that back in the 'old days', there were never pictures hanging on the walls in Japanese homes. There was a tokonoma, in which images could be displayed, but always on a temporary basis. Artwork was stored away, and only brought out for viewing when it was appropriate to do so - in season, or for a guest. It was thus always fresh to ones' eyes.

"But these days people don't want 'bare' walls, so they hang pictures. The first day the picture is there, you are happy for the decoration. The first week ... no problem. But then what happens? You know what happens; it just becomes a kind of wallpaper, and is no longer noticed.

"Much modern art is well suited to this - it is a kind of colourful decoration. But not these supremely delicate and detailed traditional woodblock prints! To appreciate one of these, you must see it close up, in the horizontal orientation, and with fresh eyes ... Then, and only then, can you understand its beauty, and appreciate the skill of the 20 or so craftsmen who made it!"

[Narrator] 20 people? But we thought that David made his prints by himself ...

[David] "A moment ago, before I turned off the overhead light, you could clearly see the image, so the man who designed it - Gakutei, in this case - would be satisfied, but the participation of all the other craftsmen was invisible.

"Of course we have the carver and printer; in my case I do both of those jobs, (although they are usually separate people). But it's not just them. This beautiful creation could not have come into being without the skills and participation of a string of other craftsmen: the man who forged the laminated steel carving tools, the men who selected, sawed, dried, and then planed the cherry blocks, the people who knew just how to select the best kind of horse hair for the printing brushes, the very skilled paper makers, the people who make the su - the screen on which the paper is rocked - the man who sizes the sheets ready for printing ... the list goes on and on and on and on."

"Of course we have the carver and printer; in my case I do both of those jobs, (although they are usually separate people). But it's not just them. This beautiful creation could not have come into being without the skills and participation of a string of other craftsmen: the man who forged the laminated steel carving tools, the men who selected, sawed, dried, and then planed the cherry blocks, the people who knew just how to select the best kind of horse hair for the printing brushes, the very skilled paper makers, the people who make the su - the screen on which the paper is rocked - the man who sizes the sheets ready for printing ... the list goes on and on and on and on."

[Camera] As David speaks this final paragraph of Part One, we see a closeup of one of the prints, on the table under soft light.

[David] "We can see all of those men in this print - if you sit quietly and look! And if any one of the links in that chain of craftsmen were to break - the production of these prints would no longer be possible. At present, some of the links are getting very shaky indeed ... and the future of our craft is far from assured."

[End Part One]

(to be continued)

This is the autumn issue of the newsletter, and late as it is, I think we're getting it out the door just in time - there are still autumn colours to see in many parts of the country.

This is the autumn issue of the newsletter, and late as it is, I think we're getting it out the door just in time - there are still autumn colours to see in many parts of the country.

I think this current project should be seen the same way. Because I do not have an established body of original work, you have to be prepared to come across things that you might not expect to see. There is no established 'David Bull style'. In that sense, this series is very much an exploration, one being supported by the people who have chosen to collect the set, even though they have no idea what is coming up next.

I think this current project should be seen the same way. Because I do not have an established body of original work, you have to be prepared to come across things that you might not expect to see. There is no established 'David Bull style'. In that sense, this series is very much an exploration, one being supported by the people who have chosen to collect the set, even though they have no idea what is coming up next. I am quite happy that the prints have this ambivalence. This is a kind of contradiction in them, and I suspect that this may turn out to become a defining characteristic of my work. Are they thus 'incoherent' or 'confused', or is the ambivalence something that can be accepted? I myself have no idea; I just make the things.

I am quite happy that the prints have this ambivalence. This is a kind of contradiction in them, and I suspect that this may turn out to become a defining characteristic of my work. Are they thus 'incoherent' or 'confused', or is the ambivalence something that can be accepted? I myself have no idea; I just make the things. So although I usually accede to media requests, and do my best to be a 'good' interviewee, when seen from my point of view, the resulting stories or programs are invariably simplified and shallow, giving nothing more than the barest outline of what I am doing.

So although I usually accede to media requests, and do my best to be a 'good' interviewee, when seen from my point of view, the resulting stories or programs are invariably simplified and shallow, giving nothing more than the barest outline of what I am doing. [Cold Open] [Camera] Rippling water flowing past mossy stones. We hear the gentle sound of the stream, as well as birdsong. Slowly, the camera pulls back and pans along the scene - a small river surrounded by greenery. As we pull back further, we realize that the camera is shooting out a window. The interior of the room begins to become visible, and as it does, the sounds change; the ripple of the river fades, and a new sound becomes audible - the faint sound of a sharp blade cutting through wood. We are in David's workshop, and he is carving. We watch.

[Cold Open] [Camera] Rippling water flowing past mossy stones. We hear the gentle sound of the stream, as well as birdsong. Slowly, the camera pulls back and pans along the scene - a small river surrounded by greenery. As we pull back further, we realize that the camera is shooting out a window. The interior of the room begins to become visible, and as it does, the sounds change; the ripple of the river fades, and a new sound becomes audible - the faint sound of a sharp blade cutting through wood. We are in David's workshop, and he is carving. We watch. [David (voice over)] "I can hear - as well as feel - when the blade needs sharpening; the knife starts to tear its way through the wood instead of slicing. It is vitally important to keep it as sharp as possible. Many of the carved lines in my prints are extremely fine; if the knife is too dull, the edge of the wood becomes slightly torn, allowing water to enter during the printing stage. The printed lines lose their delicate character ..."

[David (voice over)] "I can hear - as well as feel - when the blade needs sharpening; the knife starts to tear its way through the wood instead of slicing. It is vitally important to keep it as sharp as possible. Many of the carved lines in my prints are extremely fine; if the knife is too dull, the edge of the wood becomes slightly torn, allowing water to enter during the printing stage. The printed lines lose their delicate character ..." [Camera: as titles roll ...] Back at the carving scene in the workshop. David seems to come to the end of a particular section of the work; he puts down his tool, straightens things up a bit, and gets up from the bench. Cut to outside: view of the river, but at one side of the screen, David comes out of the workshop door, and heads upstairs. Cut to room upstairs: Dave comes in, goes to the print storage shelves, pulls a folder out, sits down, and shows it to us ...

[Camera: as titles roll ...] Back at the carving scene in the workshop. David seems to come to the end of a particular section of the work; he puts down his tool, straightens things up a bit, and gets up from the bench. Cut to outside: view of the river, but at one side of the screen, David comes out of the workshop door, and heads upstairs. Cut to room upstairs: Dave comes in, goes to the print storage shelves, pulls a folder out, sits down, and shows it to us ... [David] "Now there is no doubt, is there? This is a woodblock print! Look at it! You can see - even feel - the lovely texture of the washi. Over here there is a place where the printed lines are embossed into the body of the paper. Look there, where these colours blend together so beautifully ... And everywhere - the pigment has been taken up between the fibres of the washi; it's an exquisite sensation to see this!

[David] "Now there is no doubt, is there? This is a woodblock print! Look at it! You can see - even feel - the lovely texture of the washi. Over here there is a place where the printed lines are embossed into the body of the paper. Look there, where these colours blend together so beautifully ... And everywhere - the pigment has been taken up between the fibres of the washi; it's an exquisite sensation to see this! "Of course we have the carver and printer; in my case I do both of those jobs, (although they are usually separate people). But it's not just them. This beautiful creation could not have come into being without the skills and participation of a string of other craftsmen: the man who forged the laminated steel carving tools, the men who selected, sawed, dried, and then planed the cherry blocks, the people who knew just how to select the best kind of horse hair for the printing brushes, the very skilled paper makers, the people who make the su - the screen on which the paper is rocked - the man who sizes the sheets ready for printing ... the list goes on and on and on and on."

"Of course we have the carver and printer; in my case I do both of those jobs, (although they are usually separate people). But it's not just them. This beautiful creation could not have come into being without the skills and participation of a string of other craftsmen: the man who forged the laminated steel carving tools, the men who selected, sawed, dried, and then planed the cherry blocks, the people who knew just how to select the best kind of horse hair for the printing brushes, the very skilled paper makers, the people who make the su - the screen on which the paper is rocked - the man who sizes the sheets ready for printing ... the list goes on and on and on and on."

In the previous update to the workshop construction, I showed how we were preparing the ceiling for insulation, and the other day Sadako came over and helped me get it all stapled up in place!

In the previous update to the workshop construction, I showed how we were preparing the ceiling for insulation, and the other day Sadako came over and helped me get it all stapled up in place! The insulation batts are a nominal 10cm thick, but actually fluff up to quite a bit more, and once they were in place, we stapled an air/vapour barrier layer over them. The finishing layer - I'm planning to use thin wood strips running the length of the room - will have to wait for later, but anyway, this room should now be a lot warmer this winter!

The insulation batts are a nominal 10cm thick, but actually fluff up to quite a bit more, and once they were in place, we stapled an air/vapour barrier layer over them. The finishing layer - I'm planning to use thin wood strips running the length of the room - will have to wait for later, but anyway, this room should now be a lot warmer this winter!