Woodblock Dreams ...

Some time ago I spent a few days in London doing some research on Japanese prints (if I can use the rather formal word 'research' for what was really just some woodblock print 'sight-seeing'). In one of the museums I visited I had a chance to see something interesting in addition to the boxes of prints themselves that were brought out for my perusal; they had acquired a few of the original woodblocks that had been used to make some of the prints. These blocks were not all that old, only dating back about a hundred years, to the late Meiji period, but this was no disappointment at all - that was the period in which the carvers' skills reached their highest peak.

Seeing those blocks was quite interesting for me, as it is very difficult to learn about carving techniques from looking only at finished prints; 'reverse engineering' can only take one so far - what is invisible in the prints themselves are things like just at what angle the blade was held, or how deeply the carver cut into the wood. So I quite appreciated this rare chance. It turned out to be a bit frustrating though - the blocks were very well-used, having printed a number of editions over the years. The fine lines were all rounded on the top, and there were chips, splits and cracks here and there throughout the wood.

I found myself trying to imagine what they must have looked like when they were new, just out from 'under the knife' ... trying to imagine just how incredibly crisp and sharp those lines must have been. How beautiful those blocks must have been when they were first carved - but how could one now, in this day and age, ever get a chance to see such a thing?

Only in one's dreams ...

* * *

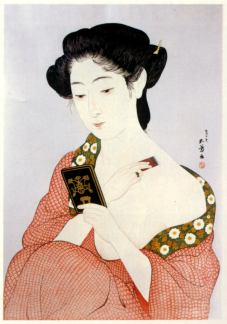

Let's step back in time a number of years, and imagine that one of the woodblock publishers one day had an idea for a new publication - a print of a rather classical type, a bijin-ga ('beautiful woman picture') featuring a lady applying traditional makeup to her face and neck. Her intricately patterned kimono would be pushed down slightly over one shoulder, and she would be looking into a small hand-held mirror, the reverse of which would be detailed in black lacquer and gold. Her coiffure would be carefully done up, but not so carefully that wisps of loose hair couldn't escape here and there around the edge of her face and neck ... incredibly tiny and delicate hairs that would give a master carver an opportunity to stretch his skills to the limit ... The print would be quite large, and would use a full masa-ban sheet of paper, just about double the size of most typical ukiyo-e prints. It would be a spectacular masterpiece!

The publisher calculated the economics of the proposed project, the special paper that would have to be ordered, the extra printing costs for the mica background he was envisaging, and he of course did not forget to include the rather staggering costs of so many 'double-size' cherry blocks. It was a close call to make, and there was no question that it would be quite a gamble. But he wanted to believe that surely buyers could be found for such a print when completed, so he held down his doubts, and decided to proceed with the project.

But one question mark still did still loom large - when completed this would indeed be an expensive print, and the market for it would not be among the tourists from overseas who were looking for a souvenir of the 'quaint' Japan they were visiting. The potential purchasers would be those people, foreigners and Japanese alike, who were connoisseurs of the woodblock print. And such people are strict! They would look at the print very closely indeed before making a purchase decision, inspecting all the critical areas, the body outlines, the face, and of course the delicate hair ... The publisher knew that the carving would have to be nothing short of magnificent, or the project would fail.

He cast his mind over the craftsmen he knew ... which one among them would be the best one to take on this job? He thought about this very important decision for quite some time, and then had an interesting idea - he would call up Nakagawa Mokurei and see if he could talk him into doing these blocks. Nakagawa-san had actually retired from carving a number of years previous to this; he had 'hung up' his tools. But perhaps he could be coaxed back into the saddle for one more job ... "Please come and do these blocks - this print is going to be a true masterpiece, and you are the only man left alive who can do it justice. Please do this for us ..."

And Nakagawa-san, whether out of obligation to the publisher, or out of pride at being selected for this special job it is difficult to say, consented to the proposal, and agreed to do the job.

For the key block, the block on which all the most delicate carving would be done, a wide slab of the finest mountain cherry was selected from the stock available. The tree had been felled, sliced into planks, and roughly dressed some years before this, and the wood had spent the intervening time slowly drying and stabilizing. The selected piece was now cut to the proper dimensions and then received its final smoothing and dressing with a series of hand planes, each one finer and trimming a thinner shaving than the one before it, until the surface of the wood was as smooth as the finest mirror. Immense care was taken in the preparation of the hanshita, the tracing that would be Nakagawa san's guide. It was not possible for any artist to draw hair lines as fine as those that he would carve, but Nakagawa-san didn't need such 'assistance' - just show him the general outline of the design, and his lifetime of carving experience and his sense of how lines should flow would do the rest.

So with everything thus ready, the work began. The old carver was soon back in the swing of the work; it took no more than a couple of hours for the old rhythms to return, and his blade sliced along the lines of the hanshita with smooth confidence. The work of cutting lines such as this can not be done in a mood of extreme care and painstaking progress, but rather must proceed with a smooth and easy naturalness. No matter how delicate the line may be, the carver's knife must slide along it as easy and naturally as the brush of the artist who originally drew the design. If not, then the resulting lines on the print would be 'hard' and lifeless.

So with everything thus ready, the work began. The old carver was soon back in the swing of the work; it took no more than a couple of hours for the old rhythms to return, and his blade sliced along the lines of the hanshita with smooth confidence. The work of cutting lines such as this can not be done in a mood of extreme care and painstaking progress, but rather must proceed with a smooth and easy naturalness. No matter how delicate the line may be, the carver's knife must slide along it as easy and naturally as the brush of the artist who originally drew the design. If not, then the resulting lines on the print would be 'hard' and lifeless.

But Nakagawa-san was a master at this. Day-by-day the carved area of the block expanded in size as he worked over first one area and then the next. Nobody was asking him to 'hurry up' ... nobody pushed him in any way ... One can suppose that the old man knew that this would be his final job, and who could fault him for wanting to make sure that this block would be a masterpiece. When all the lines had finally been incised into the wood the clearing of the wide waste areas began. In the real old days ... 'way back when' ... the block would have been turned over to less-experienced carvers for this part of the job, but Nakagawa-san kept it on his own bench, and did this himself. This was to be his masterpiece!

At last the key block was done, and when the publisher came to inspect the work he was astonished at what he saw. He had been in the business for a long long time, but never, never, had he seen a block like this. Nakagawa-san had produced ... not a simple wood block for making a wood block print, but ... a sculpture. Of course, it was functional as a block for printing, but in addition to carving all the lines, and then removing the unneeded waste between them, the old man had carefully and neatly sculpted each area of the wood into gentle curves and valleys. The carved lines - and how astonishingly finely they had been carved! - stood up clearly against the smoothly dressed background wood. The artist's design was as clear here on the block as it would later be when pressed into the soft white paper. This block itself was the masterpiece; the fact that it could then be used to make prints seemed almost irrelevant. What pride Nakagawa-san must have felt as he sat and showed it to the publisher!

At last the key block was done, and when the publisher came to inspect the work he was astonished at what he saw. He had been in the business for a long long time, but never, never, had he seen a block like this. Nakagawa-san had produced ... not a simple wood block for making a wood block print, but ... a sculpture. Of course, it was functional as a block for printing, but in addition to carving all the lines, and then removing the unneeded waste between them, the old man had carefully and neatly sculpted each area of the wood into gentle curves and valleys. The carved lines - and how astonishingly finely they had been carved! - stood up clearly against the smoothly dressed background wood. The artist's design was as clear here on the block as it would later be when pressed into the soft white paper. This block itself was the masterpiece; the fact that it could then be used to make prints seemed almost irrelevant. What pride Nakagawa-san must have felt as he sat and showed it to the publisher!

And then ... (Oh, I can't ... can't type this next sentence ...) And then ... Nakagawa-san the carver died.

Do you think that only in a dream it could have happened this way? That incredible block truly had been his final masterpiece ...

After the funeral ceremonies were over, the publisher sat in his office and looked at the block. It would not be a major problem to find another carver to complete the job - to cut the set of colour blocks that were needed to make the print. That part of the work would traditionally have been done by less experienced carvers anyway. But as he sat and studied the block, the beautifully flowing smooth surface of the carved wood surrounding the fine hair lines, he couldn't bring himself to simply 'pass it on' to the next man ... He thought for a while, and then slipped it carefully onto a shelf in his office, where he would be able to look up at it during his work, and moved on with other projects. What was in his mind as he did this? Perhaps the difficult economics of the project were starting to worry him a bit ... perhaps he simply wanted to let a polite amount of time pass after Nakagawa-san's death before asking the next carver to continue the work ... we do not know.

The days went by, the months went by ... Other projects came and went, as the business of the publishing house continued uninterrupted. The years went by, the decades went by ... That day finally came when the publisher retired, and his successor took over the business; inherited the building, the stock of prints on hand, the woodblocks for all their back catalogue of prints, and of course ... carefully wrapped and stored away, the block for the forgotten print ... The block that had been carved as the final masterpiece of a master carver, and then never used for making prints; the delicate lines still as sharp and clear as the day they had been incised, all those decades ago.

* * *

By studying carved blocks in collections and museums around the world, we can get a pretty good idea of the working methods and skills of the old carvers. But only a 'pretty good' idea. Those blocks have of course been used and re-used and re-used, and with each sheet of each re-printing the delicate lines were eroded a few more molecules by the particles of the pigment. Looking at them now is like looking at an ancient sculpture in the Egyptian desert; the centuries of blowing sand have turned the sculptor's sharply incised lines into dull and formless rounded shapes.

But imagine if somehow, somewhere, a woodblock carved by a master craftsman could have been preserved from those sands of time ... Just try and imagine how it could have happened ...

... how it could have happened ...