Karuta: Sports or Culture?

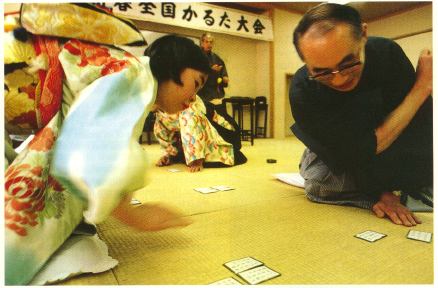

The silence in the wide

tatami room is absolute. About two dozen people, kneeling in the

formal seiza style, face each other in pairs here and there on the

mats. To us observers, they may as well be statues. Nothing moves.

Each is dressed in an elegant kimono, ranging from the muted darker

tones of those worn by the elderly ladies, to the bright patterns and

long sleeves worn by their daughters, both set off by the grey and

black hakama worn by all the men. Everybody is staring intently down

at the floor, where a number of small white cards are laid out in

neat rows between each couple. Everything is frozen in place.

An elderly gentleman, also attired in formal

hakama, sits on a cushion at the head of the room, surveying this

scene. He holds more of the cards in his outstretched hand. Suddenly

he begins to chant ...

Waga koromode ni

...

His voice is old and harsh, and he strains to

produce the higher pitch at the end of each line.

Yuki wa furi tsutsu

...

The last syllable trails off into silence. Still

nothing moves.

Naniwa gata

...

And then, just on the sound of that

'ga', the entire

room explodes in a sudden eruption of movement and noise. The old man

is perhaps still chanting, but it is impossible to make out what he

is saying above the sudden chaos. Long kimono sleeves are waving

about ... Cards have been tossed into the air, some to land far over

on the other side of the room. Everybody is talking at the top of

their voice ... People are moving around to retrieve the scattered

cards, holding them up in triumph ... The bustle of noisy activity

continues for about a minute, during which these former statues

gradually restore everything to its correct position, putting the

cards back into their neat rows, and tucking all the long kimono

sleeves back into place. The room becomes still again, and the

tableau is restored. All is silent once more. The cycle begins anew

...

Awade kono wo yo

...

What was in that chant that

it could cause such an eruption? Naniwa

gata ... 'The marsh at Naniwa ...' It is

of course, poetry. A line of a poem penned by the lady Ise just about

eleven hundred years ago. A love poem. Passed down through the

centuries both in writing and orally, it still lives today more than

a millennium after the day she created it. Everybody in this room

knows every syllable of it, and every syllable of each of the other

99 poems that will be chanted here today. For these poems are the

famous 'Hyaku-nin Isshu', One Hundred Poems from One Hundred Poets, and this is a

competition being held to determine the best player of the game known

as karuta. We are watching a sports event. But surely ... old poetry

... elegant kimono ... Shouldn't we describe this rather as a

cultural event? Perhaps it is really something of both.

In order to understand what

karuta is, it is necessary to look at three aspects of the game,

three things which 'came together' over the years to make up what we

know as karuta today.

The first of these, and most fundamental to the

game, is the poetry collection on which it is based. The Japanese

people seem always to have been enamoured of making up 'sets' or

'series' of things, whether it be a group of three 'must-see'

sightseeing locations, forty-seven famous samurai warriors,

fifty-three post stations along a highway, or, as in this case, a

collection of one hundred poems. The poems in this Hyakunin Isshu

collection are not the haiku type so common these days (with their

5-7-5 rhythm), but the older form known as waka (or tanka), which are longer, and

have a 5-7-5-7-7 rhythm. Recent manuscript discoveries seem to

confirm what historians have generally accepted for centuries, that

the collection was created by the nobleman Fujiwara no Teika in about

1235, using poems that spanned the time from the seventh century up

to his own day. He is known to have edited many books of poetry, and

to have made other collections similar to this one. Whether he was

indeed asked to make a selection of poems to decorate fusuma panels,

as some claim, or whether he needed no particular reason to make the

collection, is a matter of dispute among scholars, but what is beyond

dispute is the extremely high quality of the selection. Not the

quality of the poems themselves, which vary quite widely, but the

quality of the selection. Literally hundreds of books have been

written trying to explain why this particular hundred were chosen.

One writer shows that the poems can be placed into exactly balanced

groups based on similar themes, another shows how they can all be

placed into a 10x10 grid, each one having links to all the others

around it, yet another demonstrates that they were chosen to

represent scenes from the famous Genji Monogatari ... It is a most

intriguing literary mystery.

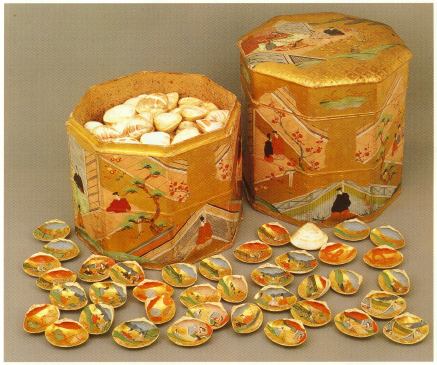

The second 'leg' of the karuta tripod can be

traced back to the Heian era, to some of the games then fashionable

among the nobility. From what we know of the daily life of this

class, many of their days must have been extremely long and dreary

indeed, sitting in prescribed locations, in prescribed clothing, and

able to speak only to certain people. Perhaps as a result of this

enforced idleness, certain games came into fashion, games which of

necessity utilized many of the things with which these people were

surrounded - poetry, calligraphy, literature, etc. One very popular

game was the kai-awase, or 'shell matching' game. On the inner surface of the two

halves of a clam or oyster shell would be painted matching scenes,

perhaps flora and fauna, or perhaps something with literary

allusions. Large sets made up of many such shells would be spread out

face down on the floor to test everyone's ability to match them up,

the same way that children still do today with playing cards. A

number of astonishingly delicate and beautiful sets of these shells

have come down to us today, including some that use written poetry,

rather than illustrations, and it is in these that we can best see

the historical link to the karuta.

The word karuta is spelled

in Japanese usually by using the katakana syllabary, thus indicating

that the word is of foreign origin. The language from which it came

is Portuguese, and it is presumed that European playing cards, the

third leg of our tripod, were first introduced into Japan by these

nanban-jin, from

about the mid-sixteenth century. Most of our knowledge of the early

days of karuta comes not from actual surviving cards themselves, but

from images of contemporary life painted on screens, the byobu-e. On

quite a number of these screens people can be seen playing with

cards, of which various types were apparently popular. It seems that

at first, playing with these cards had been something that the bushi

class had taken up, but within half a century, the games had spread

to women and children, and to all social levels of society.

The ten-sho cards, coming in sets of

72, and pretty much identical to the Portuguese cards, were the

earliest popular type, but these were replaced by the un-sun karuta,

in a completely Japanese style. These too rather quickly evolved into

something else, this being the still-famous hanafuda, the flower cards.

These transformations did not come about because people were

particularly bored with each game, but rather as a consequence of

government edicts against gambling. This was during the early days of

the Edo bakufu, when the government was attempting to regulate

practically every aspect of life for people at all levels of society.

Gambling was of course considered a highly anti-social activity, and

innumerable decrees against it were issued. But just as with pachinko

and mah-jongg in our own day, official government disapproval of a

game did not always seem to have much effect. It seems that as the

pressures against each type of game became too intense, the people

simply switched to a new, at first completely innocuous, form of

playing with cards.

With many types of cards thus common in society,

it is no surprise to find that some of the old Heian era games also

made the transition to this new form. The former kai-awase using

shells now became the e-awase, a picture matching game

using cards. These cards were produced in sets of matching pairs

containing illustrations of almost anything under the sun. Of course

the old literary themes were well represented, but even such plebeian

things as vegetables, household objects, or craftsmen at work all

served as subjects. These cards were at first all hand painted

individually, but towards the middle of the Edo era, as wood-block

printmaking became more refined, cards were mass-produced with this

technique. One theme that remained ever-popular was poetry, and it is

here that the three parts of our story now come together, and we see

the origin of the Hyakunin Isshu karuta.

Nobody can put any but the roughest date to this

event, or even hazard a guess as to who was responsible, but in

retrospect at least, it seems like a fairly inevitable development.

During those years that various forms of playing cards had been

becoming popular, the Hyaku-nin Isshu had itself developed into an

important aspect of Japanese life. Whether due to Teika's skill in

selection, or just by serendipity, knowledge of this particular set

of poems had become expected of all those who considered themselves

to be 'cultured' people, and just as they still are today, they were

then a standard theme for calligraphy practice. One common form of

this practice was to write the entire set of poems (sometimes with

accompanying illustrations) onto a single large sheet of paper, which

would then be folded many times to bring it down into a manageable

size. It needs no large leap of imagination to imagine this sheet

then being cut up into individual poems, and then even further, for

the poems themselves to be cut into two parts, to create a version of

the old matching game. The idea obviously caught on, and many such

cards were soon available, some hand-drawn, others being printed from

woodblocks. The Hyakunin Isshu karuta had been born.

This new form of karuta

turned out to have an influence in society far greater than one would

expect from a simple game. It spread knowledge of the Hyakunin Isshu

poetry to a far wider audience than it had previously enjoyed. Many

of the locations mentioned in the poems, and the amorous situations

or poetic phrases, passed into the general language of the day, and

many of these allusions are still current, even if their origin is

generally unrecognized. The popularity of the game grew over the

years, until by the Meiji era, a set of cards was to be found in

nearly every home, and learning the poetry was now a standard part of

the education of every person. An immense number of books on the

subject was published, giving not only the poems themselves and their

background, but descriptions of techniques for playing the game; how

to best memorize the poems; how to properly lay out the cards for

quickest recovery; how to win! The sport was getting serious.

At this point it is perhaps best to look at how

the game is actually played. The basic equipment for all versions is

a set of 200 small (74x52mm) pasteboard cards. 100 of these, the set

held by the chanter, contain the complete poems, one to a card, along

with a small illustration purporting to be the corresponding poet.

(These are of course all completely imaginary portraits, and now

follow standard patterns laid down during the centuries.) The other

100 cards, the tori fuda, contain no illustration, but only poetry - and only the

final phrase of the poem (the 7-7 portion). The players must thus

rely on their memory of the complete poems to direct them to the card

which matches the poem being chanted at any particular moment.

The

standard form of the game, which we got a glimpse of earlier, is

known as kyogi

(competition) karuta. The set of 100 tori fuda cards is split 50-50

between two players (or 25 each among four people). Before play

starts, each player spreads his cards out on the tatami face-up in

front of him, using any one of a number of methods. This is a point

of great importance to serious players, as not only must one be able

to retrieve one's own cards as quickly as possible, but one must also

attempt to 'steal' cards from the other side. With your own cards

placed 'just so' in your own special way, it is not necessary to even

look down when it comes time to find them, and you can thus

concentrate on catching cards from your opponent. The basic idea of

course, is to end up with the most cards at the end of the game. When

all is in place, the chanting of the poems begins. As everybody's

knowledge of the poetry is so complete, it is never necessary for the

reader to reach the last stanza of the poem before the players

recognize which card to retrieve, but there are some interesting

quirks. In seven of the poems, the first syllable is unique to the

set of one hundred, and thus enough to identify the poem. The

explosion of activity comes as soon as the first sound is out of the

reader's mouth. But for all the rest of the poems, the players must

wait until the first unique syllable is spoken, and in some cases,

this may be as far into the poem as the sixth syllable. In the

example we saw earlier, 'Naniwa gata ...', the players had to wait

until the 'ga' was spoken to distinguish the poem from a similar one

which starts 'Naniwa eno ...' But of course, if that 'other' poem has

already been taken, one need not wait that long, so it is always

necessary to keep mental track of which cards have been removed from

play.

The

standard form of the game, which we got a glimpse of earlier, is

known as kyogi

(competition) karuta. The set of 100 tori fuda cards is split 50-50

between two players (or 25 each among four people). Before play

starts, each player spreads his cards out on the tatami face-up in

front of him, using any one of a number of methods. This is a point

of great importance to serious players, as not only must one be able

to retrieve one's own cards as quickly as possible, but one must also

attempt to 'steal' cards from the other side. With your own cards

placed 'just so' in your own special way, it is not necessary to even

look down when it comes time to find them, and you can thus

concentrate on catching cards from your opponent. The basic idea of

course, is to end up with the most cards at the end of the game. When

all is in place, the chanting of the poems begins. As everybody's

knowledge of the poetry is so complete, it is never necessary for the

reader to reach the last stanza of the poem before the players

recognize which card to retrieve, but there are some interesting

quirks. In seven of the poems, the first syllable is unique to the

set of one hundred, and thus enough to identify the poem. The

explosion of activity comes as soon as the first sound is out of the

reader's mouth. But for all the rest of the poems, the players must

wait until the first unique syllable is spoken, and in some cases,

this may be as far into the poem as the sixth syllable. In the

example we saw earlier, 'Naniwa gata ...', the players had to wait

until the 'ga' was spoken to distinguish the poem from a similar one

which starts 'Naniwa eno ...' But of course, if that 'other' poem has

already been taken, one need not wait that long, so it is always

necessary to keep mental track of which cards have been removed from

play.

When we met the elderly gentleman reading the

poems a few pages back, the first two lines we heard were actually

the 'left-over' final two seven-syllable lines of the previous poem.

He had paused mid-way through reading it, after the explosion of

activity, to give time for order to be restored to the room. He

always starts anew with these two lines, to provide a transition to

the next poem, letting the final syllable hang in the air ...

During a kyogi karuta match, there is certainly no

time during play to reach down leisurely to actually pick up the

cards. At the instant the chanted poem is recognized, the two

contestants both dive for the corresponding card, each trying to be

the first to get a finger on it, and flick it off to one side. The

movement is far faster than the eye of the observer can follow. The

action gets particularly tense towards the end of every game, when

the number of cards left in play is small, and it is then that the

player with the fastest reflexes will triumph. Top champions are thus

usually fairly young, still with good reaction times, but it is

fascinating to watch a competition involving quite elderly ladies.

They slowly fold themselves into place before their cards, stretch

lazily, chat a bit with their neighbours ... but once that poem is

recognized ... it is as though a snake has darted out from each

kimono sleeve!

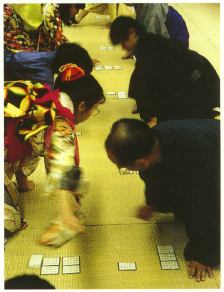

Variations on the standard kyogi karuta include

chirashi tori,

in which the 100 cards are spread out randomly on the floor in front

of any number of players, each of whom then tries to collect more

than the others, and genpei gassen, where the cards are split 50-50

between two teams rather than two individuals. A relay version of

this is also played, with the members of each team playing in turn.

The form of the game used to introduce children to karuta is known as

bozu-meguri. The children, who may know nothing of the poetry yet,

play by using the illustrations found on the reader's set of 100

cards, winning or losing cards depending on the 'luck of the draw'.

As they get older, listening to their elders play 'real' karuta, they

gradually become familiar with the poems.

As for the physical makeup of the cards

themselves, although the form is fairly standardized now, that is a

fairly recent innovation. Cards were formerly made in many shapes and

sizes, and not only from pasteboard. Elegant sets were fashioned in

lacquered finishes, or drawn on slips of thin wood. Well-known

painters down the years have turned out sets of cards, perhaps the

most famous of which is the much-photographed set by Ogata Korin,

backed with fine gold foil, and of which reproduction sets sell for

as much as 1,100,000 yen. In the Edo era it was apparently common for

sets of cards to be produced by relatively upper-class people, as

they had both the time, and the elegant calligraphy skills that were

required. One drawback to this of course, was that cards produced in

such a way were quite difficult to read. This was especially so when

the tori fuda were written in complicated Chinese characters, as was

inevitably the case back in those times. It was in the mid-Meiji era

that a newspaper company had the idea of producing sets of cards

written using the cursive hiragana syllabary, which could be read

easily by anyone, even young children. To give an impetus to the sale

of their new cards, they began to organize large-scale competitions,

and it is here that we see the origin of today's nationally organized

groups and competitions. (This Meiji-era burst of popularity in

karuta saw the birth of another Japanese institution - the Nintendo

company, of video game fame, who started out as producers of karuta

and hanafuda, which they still make. Home entertainment has come a

long way in a hundred years ...)

It is also in those early newspaper competitions

that we find the beginning of the connection between karuta and the

New Year. Although most Japanese assume that karuta has been a New

Year's custom for centuries, such an association in fact only dates

back to Meiji 37, to one of these large newspaper competitions. But

the association is now very strong, and playing karuta has become

part of the standard repertoire of New Year activities in most homes

around the country. The national competitions to select the karuta

'queen' and her male counterpart take place at this time of year, and

many TV news broadcasts in early January feature scenes of karuta

playing. To many Japanese now it's just not New Year without some

karuta action!

But strong as this association may be, the playing

of karuta is definitely not restricted to this season. In community

centres around the country, and in most Junior and Senior high

schools and colleges, one can find 'circles' devoted to studying and

practicing karuta. "It's important that children are exposed to this

tradition," a local teacher who guides one such group said. "No one

can really understand our history and language without a knowledge of

these poems." But when pressed as to whether children could really

understand the poetry, much of which is full of convoluted allusions

and archaic word play, he replied that the 'meaning' was not

important. It was enough that they simply get a general idea of the

image the poet was trying to convey. "More importantly, the 31

syllables of each poem must roll off the tongue smoothly, with no

hesitation. Even though these poems are well documented and written

down, we must think of them as an oral heritage, and each one of us

has a responsibility to pass them on to future generations."

From

the point of view of an English-speaking foreigner, one quite

striking thing about the Hyakunin Isshu tradition is the vastness of

the historical time span involved. The earliest poem in the series

was written by the Emperor Tenchi in the seventh century, some

1300-odd years ago, and this poem is still remembered by a very large

proportion of the population of these islands, more than fifty

generations later! And remembered not by scholars of ancient

literature, but by normal people - people who thus have a measuring

stick with which they can form in their minds an image of the long

history of their country. It is difficult to think of an equivalent

in Western literature. We have Greek plays from two thousand years

ago, but if you were to stop your man-on-the-street and ask for a few

quotations ... Perhaps the only things in the West that survive from

such a long time ago in anything like such a popular form, are

religious writings such as the bible. It makes an interesting

contrast: one society holding up a bible as a pillar of cultural

tradition, and the other choosing to remember instead, a collection

of love poetry!

From

the point of view of an English-speaking foreigner, one quite

striking thing about the Hyakunin Isshu tradition is the vastness of

the historical time span involved. The earliest poem in the series

was written by the Emperor Tenchi in the seventh century, some

1300-odd years ago, and this poem is still remembered by a very large

proportion of the population of these islands, more than fifty

generations later! And remembered not by scholars of ancient

literature, but by normal people - people who thus have a measuring

stick with which they can form in their minds an image of the long

history of their country. It is difficult to think of an equivalent

in Western literature. We have Greek plays from two thousand years

ago, but if you were to stop your man-on-the-street and ask for a few

quotations ... Perhaps the only things in the West that survive from

such a long time ago in anything like such a popular form, are

religious writings such as the bible. It makes an interesting

contrast: one society holding up a bible as a pillar of cultural

tradition, and the other choosing to remember instead, a collection

of love poetry!

What then would the Emperor Tenchi think of that

karuta competition we visited a few pages back? Would he be appalled

to see his poetic creation used as the basis for such a 'sporting'

activity, or perhaps he would rather be content that it still

survives, being studied, memorized and analyzed, more than 1300 years

later. And studied and analyzed it certainly is. In any local library

anywhere in the country, one will find an extensive shelf of books

devoted to Hyaku-nin Isshu and karuta playing, to which additions are

made regularly as new commentators add their theories and

elucidations of the subject. And in a development that would surely

surprise the old emperor and his 99 companions, Hyakunin Isshu has

gone international. The earliest complete translation of the series

into English was published as far back as 1892, and that early effort

has been followed by many more in the intervening years, in other

languages also. Hyaku-nin Isshu may have been born in Japan, and is

certainly Japanese culture, but it is no longer only Japanese.

Although it seems rather doubtful that the Japanese sport of karuta

will one day follow Japanese judo to reach the Olympic Games, it is

on its way to becoming part of the general culture of mankind.

Now, if everybody is ready ...

Akinota no kariho no

...

David Bull, 1996