Around the Block

Although I moved to Japan in 1986 - around 24 years ago - that was not the first time I had been here. On two previous occasions I had come over for a visit, for a couple of months each time. I was working for a music company in Canada in those days, but was gradually developing an interest in Japan, and in Japanese printmaking. Those two early trips had been mostly for getting introduced to Japan, so my then-wife and I travelled around quite a bit, and of course spent a lot of time down in the countryside where her family lived.

But I did manage to squeeze in a bit of 'research' on printmaking. I haunted used book shops for anything on the topic, and during the first visit, picked up some student grade tools from an art supply shop. I was also the recipient of a couple of interesting gifts; we visited two print publishers to purchase some of their work, and both of them - after hearing of my plans to work on traditional printmaking - let me have a couple of small woodblocks (blank blocks) from their stock. Once back in Canada I used these for practice and training, thus discovering for myself just how important it was to have the proper wood. So when I came on the second visit, a major item on my 'to do' list was to order some blank blocks to send back to Canada.

One of those publishers had given me the contact information for Ita Kane, the last remaining block supplier in Tokyo, run by the Shimano family, and I visited them one day to talk about wood.

Now when you are buying wood for traditional printmaking, you usually have a specific project in mind, and order blocks to suit. Some will need to be hard and dense - for the key lines in the image, or such things as fine hair carving - and others should be softer and without pronounced grain - these are to print smooth and flat colour. Back in those days, I was certainly not very good at this craft, but I wasn't just hacking around at random. When I look at the prints that I made before coming to Japan, I see experiments of different types: prints in black and white, prints in colour; prints with outlines, prints with none; reproductions of old ukiyo-e, and (clumsy) originals. I had no idea where this was all going, but bit by bit I was building my skills, in a kind of scattershot fashion.

Now when you are buying wood for traditional printmaking, you usually have a specific project in mind, and order blocks to suit. Some will need to be hard and dense - for the key lines in the image, or such things as fine hair carving - and others should be softer and without pronounced grain - these are to print smooth and flat colour. Back in those days, I was certainly not very good at this craft, but I wasn't just hacking around at random. When I look at the prints that I made before coming to Japan, I see experiments of different types: prints in black and white, prints in colour; prints with outlines, prints with none; reproductions of old ukiyo-e, and (clumsy) originals. I had no idea where this was all going, but bit by bit I was building my skills, in a kind of scattershot fashion.

By the time of this visit to the woodshop, I was trying to look forward and think about the possibility of producing a series of prints that could be sold. I knew my skills weren't at that level yet, but if you don't look ahead to where you want to be at some point, you'll never get there, so I planned a project. It occurred to me to create a project to reproduce some of the early-day ukiyo-e, and I settled on a famous series of 12 designs by Hishikawa Moronobu, entitled Yoshiwara no Tei, which depicted scenes from the Yoshiwara pleasure quarter. (I should perhaps mention that these are 'genre' scenes, nothing erotic or possibly embarrassing at all.)

So one day during that second visit to Japan (this was in January 1984) I placed an order with the Shimano family for a set of six blank cherry blocks of the appropriate size, asking them to supply their 'best' wood. I ordered a few other blocks too, and arranged for them all to be shipped by sea parcel back to Canada. My Japanese was in those days rudimentary at best, so I have no real memory of our 'conversations', nor do I have any understanding of what they thought of all these plans. But they did the job, and the wood was eventually received in Canada.

I didn't touch it.

The blocks were magnificent. The wood, planed by the older master of the shop, had such a mirror finish that - and yes, I tried this! - two pieces placed face to face could not be separated again, and had to be slid apart sideways. I could not bring myself to cut them. I knew that my skills were still rudimentary, and felt that it would be a crime to spoil these blocks. I kept them carefully wrapped up, to wait for the day when I would be 'ready'.

A couple of years later, I quit the job in the music shop, and brought my young family to Japan, where we found an apartment in Hamura, on the west outskirts of Tokyo. We came with only such clothes as we could carry in a backpack (and one favourite toy each for the girls!), and left all our other possessions in storage in Vancouver, including those blocks.

I began teaching English to feed us, while slowly working on the printmaking skills on the side. I ordered new blocks as they were required, and after I managed to get the printmaking career up and running, with the start of the long poetry series, I became a regular customer of the Shimano family, getting fresh blocks from them every month.

The years went by. I became divorced from the children's mother, and then a few years after that, the two girls returned to Canada for their schooling. The printmaking work continued, month after month, year after year. One summer, I was back in Canada visiting my daughters, and while there, cleaned out the old storage locker and arranged for the contents to be shipped over to Japan. Fifteen years after their original journey overseas, the set of six beautiful blocks returned 'home'.

I still didn't touch them.

Now and again, I would open the box and take out the topmost piece of wood. I would turn it over in my hands, marvelling yet again at its beautiful smoothness, and thinking about using it ... But each time, I came to the same conclusion. Not yet. I'm not ready yet.

When I purchased my new home in Ome, the blocks of course came here with me, and I made sure they were stored in a room with good air circulation, where they would remain safe from mold and damp. In 2004, when I was planning the 'Beauties of Four Seasons' series, which was going to need very high quality wood, I again looked at them, but again came to the same conclusion. Not yet. I ordered fresh blocks for that project, even though by this time, the quality of wood available was far lower than it had been when I first began buying blocks. This fact of course made the 'value' of these blocks even higher. They were now not just 'very good' blocks, they had become literally irreplaceable.

I think by now you can guess where this story is going.

Yes, 26 years after they were prepared for me, the blocks are still here. Still untouched. And now, I am terrified of them.

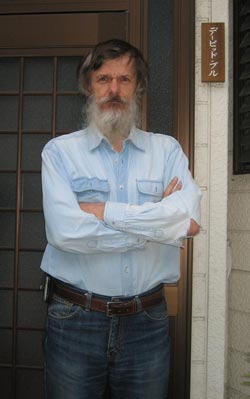

I can safely say without it being braggadocio, that I have reached a level where I am one of the finest traditional wood-cutters working. Nobody knows who is 'the best', and that is a bit meaningless anyway. But my point is that if there is anybody on this planet who has earned the right to cut these blocks, and who has the skills to do so without spoiling them, it is I.

But I can't bring myself to do it. As good as I am at this work, when I sit quietly and study the best carving of the old days, I can't help but hear one of those old craftsmen saying to me, "You're a promising talent! Keep at it, and maybe one day you'll be ready for wood like this ..."

But next year I'll be 60. Sixty! What does it mean to say 'keep at it' or 'one day' to a sixty-year-old woodcutter, especially one whose eyesight is - let's be polite - not what it used to be?

I'm having a good run through life, and at many stages along the way, I have not been afraid to 'seize the moment' and make decisions that have had far-reaching consequences. I'm not an indecisive person. But on this one I am paralyzed.

What the hell should I do with these things?

The previous issue of this newsletter marked 20 full years of publication, and this issue too we have a major milestone to observe, although this one is a bit more substantial!

The previous issue of this newsletter marked 20 full years of publication, and this issue too we have a major milestone to observe, although this one is a bit more substantial!

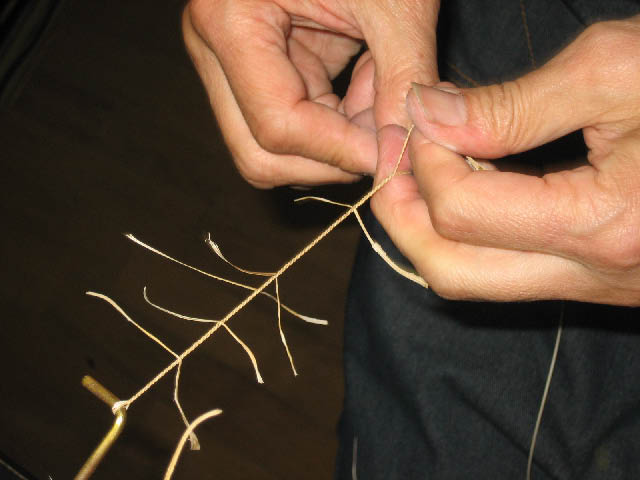

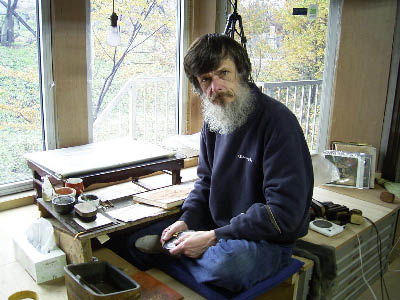

Now when writing about a basically old-fashioned craft like ours, it is very common for the story to be one of complaint about how 'things were better in the good old days'. But I have the great pleasure to report that when it comes to obtaining a good baren, this is not the case. The technique of making a true hon baren is being kept alive and well by Hidehiko Goto, working in a tiny workshop in his home in Oiso, Kanagawa, absolutely jammed with tools and supplies. I went to see him last week ...

Now when writing about a basically old-fashioned craft like ours, it is very common for the story to be one of complaint about how 'things were better in the good old days'. But I have the great pleasure to report that when it comes to obtaining a good baren, this is not the case. The technique of making a true hon baren is being kept alive and well by Hidehiko Goto, working in a tiny workshop in his home in Oiso, Kanagawa, absolutely jammed with tools and supplies. I went to see him last week ...

Stacked in every corner of his workshop are bundles of bamboo sheaths waiting to be used in his work - for both the construction of the inner coil of the baren and for its outer covering. Obtaining a good supply of high-quality bamboo is Goto-san's biggest headache by far. The weather during the bamboo growing season is a major factor affecting the supply in any given year, but over and above that is the fact that because so few people use bamboo skins these days (whether for baren making, or the old ways of wrapping food), nobody bothers to collect them anymore, and they simply rot on the ground where they fall.

Stacked in every corner of his workshop are bundles of bamboo sheaths waiting to be used in his work - for both the construction of the inner coil of the baren and for its outer covering. Obtaining a good supply of high-quality bamboo is Goto-san's biggest headache by far. The weather during the bamboo growing season is a major factor affecting the supply in any given year, but over and above that is the fact that because so few people use bamboo skins these days (whether for baren making, or the old ways of wrapping food), nobody bothers to collect them anymore, and they simply rot on the ground where they fall.

Sometime around 9:00 that morning, my bank is taking an automatic transfer of funds from my account - the final transfer in a series that began exactly ten years ago. Yes, I have come to the end of my mortgage, and this Ome house has now become completely paid for. Free at last!

Sometime around 9:00 that morning, my bank is taking an automatic transfer of funds from my account - the final transfer in a series that began exactly ten years ago. Yes, I have come to the end of my mortgage, and this Ome house has now become completely paid for. Free at last!

Now when you are buying wood for traditional printmaking, you usually have a specific project in mind, and order blocks to suit. Some will need to be hard and dense - for the key lines in the image, or such things as fine hair carving - and others should be softer and without pronounced grain - these are to print smooth and flat colour. Back in those days, I was certainly not very good at this craft, but I wasn't just hacking around at random. When I look at the prints that I made before coming to Japan, I see experiments of different types: prints in black and white, prints in colour; prints with outlines, prints with none; reproductions of old ukiyo-e, and (clumsy) originals. I had no idea where this was all going, but bit by bit I was building my skills, in a kind of scattershot fashion.

Now when you are buying wood for traditional printmaking, you usually have a specific project in mind, and order blocks to suit. Some will need to be hard and dense - for the key lines in the image, or such things as fine hair carving - and others should be softer and without pronounced grain - these are to print smooth and flat colour. Back in those days, I was certainly not very good at this craft, but I wasn't just hacking around at random. When I look at the prints that I made before coming to Japan, I see experiments of different types: prints in black and white, prints in colour; prints with outlines, prints with none; reproductions of old ukiyo-e, and (clumsy) originals. I had no idea where this was all going, but bit by bit I was building my skills, in a kind of scattershot fashion.