Forgotten Beauty of Woodblock Prints (IV)

In the first three parts of this ‘documentary’ series, Dave introduced us to some of the reasons he has found the world of Japanese traditional prints to be so absorbing. In this episode, we’ll explore how this interest has expressed itself in the creation of his own works.

The Forgotten Beauty of Japanese Woodblock Prints

[Part Four - A 20-year Journey ...]

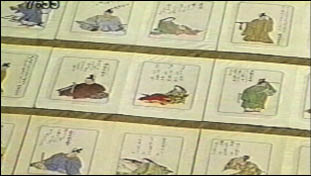

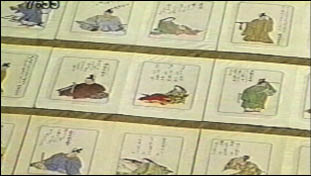

[Camera] We are in a darkened auditorium; a pool of light shines down onto the stage. Nobody is there at first. But as the camera moves closer we see that the stage is covered with a series of images mounted on display panels. Zooming in we see that they are woodblock prints - traditional designs of men and women in court dress, each person paired with a panel of Japanese calligraphy. David and an interviewer are talking as they look at the prints on display:

[Camera] We are in a darkened auditorium; a pool of light shines down onto the stage. Nobody is there at first. But as the camera moves closer we see that the stage is covered with a series of images mounted on display panels. Zooming in we see that they are woodblock prints - traditional designs of men and women in court dress, each person paired with a panel of Japanese calligraphy. David and an interviewer are talking as they look at the prints on display:

[Interviewer] “How many are there? Did you really make all these yourself? How long did it take you?”

[David] “Well, there are an even hundred of them of course - that’s why it’s called the ‘Hyakunin Isshu’ (One hundred poets - One poem each). And yes, I made the entire series by myself - working without any assistants at all - carving every block, and printing every colour. It took quite a long time indeed; at the very beginning I estimated that it would take me ten years to produce the entire series, and that turned out to be exactly true - January 1989 through December 1998.”

[Interviewer] “How old were you when you started this project?”

[David] “I was 37. I can guess your next question - how could I possibly begin a project that wouldn’t be completed for ten years! - but that’s actually easy to answer; it was because the project seemed ‘too big’ and too difficult! I had come to a point in my life where I was starting to feel that ‘Dave, if you are going to make a mark, you had better get busy; you aren’t getting any younger!’ I’m not so athletic - climbing Mt. Everest isn’t my style. So I kind of invented my own Mt. Everest - ‘There it is Dave, start climbing!’”

[Interviewer] “Was it possible for you to maintain your interest through a project that took such a long time?”

[David] “Oh, yes! There is so much depth in the set of designs that I selected for the project (created by Katsukawa Shunsho in 1775). The personalities of the individual poets are well expressed, there is endless variety in the clothing patterns, and of course learning to read the ancient calligraphy was a huge challenge too.

“The Hyakunin Isshu is one of the main pillars of Japanese classical literature, and creating this print series was the equivalent of giving myself a Master’s degree in Japanese culture and history!”

“The Hyakunin Isshu is one of the main pillars of Japanese classical literature, and creating this print series was the equivalent of giving myself a Master’s degree in Japanese culture and history!”

[Interviewer] “Did you get a grant of some kind to subsidize this large project?”

[David] “No, no ... I would never have done anything like that. In the beginning, I had no help at all; I was teaching English in those days, making prints in my spare time. But as the series became established, collectors joined one by one, and after a couple of years, I was able to put away the language textbooks and become a full-time printmaker. And do you know, a number of those early supporters are still with me, collecting every print that I have made! It also helped that the Japanese media found the project interesting, and during those years I was frequently featured on TV programs. I even used to get stopped on the street and asked for my autograph, something that hasn’t happened to me in years now! (laughs)”

[Interviewer] “What are your main memories of that period in your printmaking career?”

[David] “Well, it was quite a roller coaster; a lot of things can happen in ten years! In the early days there was severe financial pressure, and I was also far from confident in my ability to pull the whole thing off satisfactorily. But as the years went by, my skills - and my confidence - grew, and as I neared the end of the project, I began to feel quite sad that it was coming to an end!”

[Interviewer] “What did happen then? After all, once a mountaineer has climbed Everest, what can they do to top that?”

[David] “Well, the mountaineer comes back from Everest, and heads out onto the lecture circuit to talk about his achievement; perhaps he even writes a book about his adventure. I could have done much the same sort of thing. Because of all the media attention, orders were stacked up to the roof, and everybody wanted to hear about this guy and the ‘big’ thing that he had done. I heard the expression ‘your lifework!’ again and again.

“But you know, I really wanted to avoid the situation where I would always be known as the ‘Hyakunin Isshu Man.’ I was only 47; who wants his ‘lifework’ to be over at 47?”

“So although I of course enjoyed the attention that came my way at the close of the project, I began another project immediately; I announced the creation of my Surimono Album series, and had the first print done not even one month after the final exhibition of the Hyakunin Isshu project.”

[Interviewer] “Another Mt. Everest?”

[David] “Well, yes and no. I didn’t propose another ten-year project; this was an open-ended series, that turned out to comprise 50 prints issued over a five year span.”

[David] “Well, yes and no. I didn’t propose another ten-year project; this was an open-ended series, that turned out to comprise 50 prints issued over a five year span.”

[Interviewer] “What was the theme of that series?”

[David] “When I was just starting out on it, the basic concept was to produce ‘delicate, finely-detailed prints, without regard for the economics of production.’ That pretty much describes the surimono prints made in the old days. But as things got going, a different kind of focus became clear - the series turned into a kind of five-year-long ‘post-graduate apprenticeship’ for me.

“During the ten years of the previous Hyakunin Isshu series I had always been ‘held back’ by the fact that - because those prints were a unified series of designs - I was unable to explore the use of many of the varied techniques of making woodblock prints. I was ‘trapped’ in 1775, as it were. The Surimono Album series thus became for me an opportunity - no, a challenge - to train myself in all the wonderfully varied techniques used over the past three hundred years, by both carvers and printers.

“For each and every one of the 50 prints, I selected a design with that kind of thought uppermost: ‘How on earth did they do that?’ or ‘Am I really going to be able to carve and print this?’

“I worked completely without a net; there was no backup plan for each print. The collectors - who had pre-ordered each annual set of ten prints - waited eagerly to see what would be in each package. It was up to me not to disappoint them!”

[Interviewer] “And how did it work out?”

[David] “That’s difficult for me to answer. Not because I don’t know the answer, but because I’m supposed to be modest!

“But OK, speaking honestly, I think the set of 50 prints represents a stunning achievement - much more so than the previous set of 100 Hyakunin Isshu prints. There are prints in this series that are carved with a taste and delicacy fully characteristic of the finest work of the old days, and yet I am only a ‘part-time’ carver - I also did all the printing!

“When I look back at it now, the phrase ‘I can’t believe I ate the whole thing!’ comes to mind. The series represents a physical ‘encyclopedia’ of traditional Japanese printmaking techniques. I issued ten prints each year - most of them with many colours - in batches of 200 copies each. It’s perhaps a bit too soon for me to say this, but I suspect that I will never again have that kind of boundless energy!”

“When I look back at it now, the phrase ‘I can’t believe I ate the whole thing!’ comes to mind. The series represents a physical ‘encyclopedia’ of traditional Japanese printmaking techniques. I issued ten prints each year - most of them with many colours - in batches of 200 copies each. It’s perhaps a bit too soon for me to say this, but I suspect that I will never again have that kind of boundless energy!”

[Interviewer] “I’m a bit nervous about asking you what came next; surely you’re not going to talk about another Mt. Everest!”

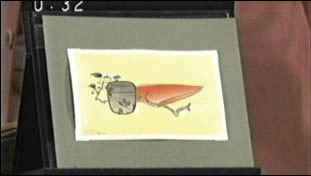

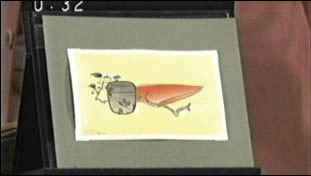

[David] “No you’re right, I think I had better stop using that expression. The print series that came next - Beauties of Four Seasons - was in a sense, simply an extension of the Surimono Albums. The difference was in the scale.

“The printing process becomes exponentially more difficult as the print size increases. Working at the relatively small scale of the Surimono Albums was all very well, but it was time for me to try my hand at something larger. Each print in this series - there were four in all - depicted a classical beauty from a different period in history, and was chosen to fit my habitual criteria: be a personal challenge to produce, be of artistic interest, and be interesting to the collectors.

“I’m beginning to sound like a broken record here, but yet again, the project met all these expectations. Perhaps the best way for me to explain the way I feel about my ‘Beauties’ series is to say that if there were a sudden fire in my studio, and I could carry out only one folio of prints ...”

[Interviewer] “I see ... Well, I promise not to tell any of your other ‘children’ what you said! You mentioned earlier that you have been making a new set of prints each year; can you elaborate on that for us?”

[David] “Well, everything we’ve discussed so far worked that way; the Hyakunin Isshu series was broken up into annual sets of 10 prints each, as were the Surimono Albums. It’s a reflection of two things: first, that all through those years I held an annual exhibition each January to showcase the prints completed in the previous year, and second, that each of the annual sets represented a convenient ‘package’ for the collectors. I never sold the prints individually.

“The next series I created was also a one-year project - the Hanga Treasure Chest. What an adventure that one was! Not four prints, not ten prints ... this series had 24!”

“The next series I created was also a one-year project - the Hanga Treasure Chest. What an adventure that one was! Not four prints, not ten prints ... this series had 24!”

[Interviewer] “In one year? That’s just about one every two weeks!”

[David] “Yes indeed! That’s exactly the schedule I set out to meet - promising the collectors that they would find a ‘present’ in their mailbox every second Monday morning. And they did!”

[Interviewer] “These must have been smaller prints?”

[David] “Yes of course; these were the Japanese hagaki (postcard) size. But as usual for me, even though they were small in dimension, they weren’t small in ‘concept’; they cover a great deal of ‘territory’ in their selection, and again, are full of interesting detail. It was a glorious year of work, but as you might imagine, the two-week deadlines created quite a bit of pressure. When it came time to plan the next project, you can perhaps guess what happened ...”

[Interviewer] “Back to the ten-prints-a-year pattern?”

[David] “No. I over-reacted; I proposed a ‘series’ with just a single print - a reproduction of a wonderful design from the early 1700s by Kaigetsudo Ando, mounted as a scroll.”

[David] “No. I over-reacted; I proposed a ‘series’ with just a single print - a reproduction of a wonderful design from the early 1700s by Kaigetsudo Ando, mounted as a scroll.”

[Interviewer] “Why do you say ‘over-reacted’?”

[David] “Well, the idea was to get it carved and printed, mounted in scroll format, and sent out to the collectors all during the calendar year, but that turned out to be impossible - it was just too much work. It took me nearly a year and a half in all, throwing my long-running ‘one set per year’ tradition out of whack, something I have not yet managed to get back in order!”

[Interviewer] “Before we move on to have a look at your current work, I’d like to ask about the people who are purchasing your prints. You keep referring to them as ‘collectors’; are these people mostly ‘art collectors’ then?”

[David] “Not for the most part; I think that very few of them would refer to themselves that way. They are not specialists at all. Their particular motivations vary, but all of them seem to share a feeling that what I am doing is of value to our society and thus deserving of support.

“And as my appetites are modest, my prints have never been expensive, so it is easy for them to help!”

[End Part Four]

In the next issue, in Part Five, Dave attempts to answer the question he was frequently asked during those years: ‘How can you be satisfied being ‘only’ a craftsman ...?’

I see that by the old traditional calendar we are now actually in ‘autumn’, but the weather here in Ome is quite hot and muggy, and after all, we are still in August, so calling this the ‘summer issue’ seems most natural to me.

I see that by the old traditional calendar we are now actually in ‘autumn’, but the weather here in Ome is quite hot and muggy, and after all, we are still in August, so calling this the ‘summer issue’ seems most natural to me.

[Camera] We are in a darkened auditorium; a pool of light shines down onto the stage. Nobody is there at first. But as the camera moves closer we see that the stage is covered with a series of images mounted on display panels. Zooming in we see that they are woodblock prints - traditional designs of men and women in court dress, each person paired with a panel of Japanese calligraphy. David and an interviewer are talking as they look at the prints on display:

[Camera] We are in a darkened auditorium; a pool of light shines down onto the stage. Nobody is there at first. But as the camera moves closer we see that the stage is covered with a series of images mounted on display panels. Zooming in we see that they are woodblock prints - traditional designs of men and women in court dress, each person paired with a panel of Japanese calligraphy. David and an interviewer are talking as they look at the prints on display: “The Hyakunin Isshu is one of the main pillars of Japanese classical literature, and creating this print series was the equivalent of giving myself a Master’s degree in Japanese culture and history!”

“The Hyakunin Isshu is one of the main pillars of Japanese classical literature, and creating this print series was the equivalent of giving myself a Master’s degree in Japanese culture and history!” [David] “Well, yes and no. I didn’t propose another ten-year project; this was an open-ended series, that turned out to comprise 50 prints issued over a five year span.”

[David] “Well, yes and no. I didn’t propose another ten-year project; this was an open-ended series, that turned out to comprise 50 prints issued over a five year span.” “When I look back at it now, the phrase ‘I can’t believe I ate the whole thing!’ comes to mind. The series represents a physical ‘encyclopedia’ of traditional Japanese printmaking techniques. I issued ten prints each year - most of them with many colours - in batches of 200 copies each. It’s perhaps a bit too soon for me to say this, but I suspect that I will never again have that kind of boundless energy!”

“When I look back at it now, the phrase ‘I can’t believe I ate the whole thing!’ comes to mind. The series represents a physical ‘encyclopedia’ of traditional Japanese printmaking techniques. I issued ten prints each year - most of them with many colours - in batches of 200 copies each. It’s perhaps a bit too soon for me to say this, but I suspect that I will never again have that kind of boundless energy!” “The next series I created was also a one-year project - the Hanga Treasure Chest. What an adventure that one was! Not four prints, not ten prints ... this series had 24!”

“The next series I created was also a one-year project - the Hanga Treasure Chest. What an adventure that one was! Not four prints, not ten prints ... this series had 24!” [David] “No. I over-reacted; I proposed a ‘series’ with just a single print - a reproduction of a wonderful design from the early 1700s by Kaigetsudo Ando, mounted as a scroll.”

[David] “No. I over-reacted; I proposed a ‘series’ with just a single print - a reproduction of a wonderful design from the early 1700s by Kaigetsudo Ando, mounted as a scroll.”

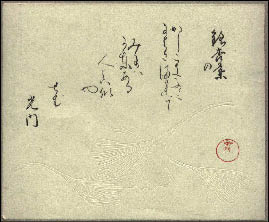

I mentioned that Tauchi-san has been involved with my work, and the print image shown here is just one example. I wanted to make a print incorporating a certain old poem, and she graciously consented to write it for me. I was very happy with the work, found it a joy to carve and print, and have had no hesitation in calling on her on other occasions; she did the calligraphy for the covers of the books in my current ‘My Solitudes’ series, as well as doing the lettering by hand on all the paulownia boxes for my scroll project - a very large job indeed!

I mentioned that Tauchi-san has been involved with my work, and the print image shown here is just one example. I wanted to make a print incorporating a certain old poem, and she graciously consented to write it for me. I was very happy with the work, found it a joy to carve and print, and have had no hesitation in calling on her on other occasions; she did the calligraphy for the covers of the books in my current ‘My Solitudes’ series, as well as doing the lettering by hand on all the paulownia boxes for my scroll project - a very large job indeed!

About a year ago in this newsletter, I included a small item introducing you to a new activity that my daughter Himi was then involved with - making purses and selling them online.

About a year ago in this newsletter, I included a small item introducing you to a new activity that my daughter Himi was then involved with - making purses and selling them online. They are getting very enthusiastic press reviews on their products: newspapers are running stories about the business, well-known ‘fashionista’ bloggers are raving about the clutches, they have been included in fashion shows, and the girls have even started to get TV coverage.

They are getting very enthusiastic press reviews on their products: newspapers are running stories about the business, well-known ‘fashionista’ bloggers are raving about the clutches, they have been included in fashion shows, and the girls have even started to get TV coverage.