Unlike many people, I have a job that leaves a clearly visible 'trail' behind me that shows just how well (or not!) I am doing my work. 'Job performance' is not so easily measured for some, but in my case, it is an inescapable element of my life. There sit the finished prints - a long line of them extending back many years - and they constitute a record that can be easily examined by anybody who cares to ask the question "How well is this guy doing his job?"

The question is relative of course. The prints I made back at the beginning of my Hyakunin Isshu series look terrible to me now, although at the time I was very pleased with them. Back then I had no idea at all just how difficult this job was; I knew I was inexperienced, with a long way to go to develop my skills, but at the time I had not yet realized that this job - making reproductions of traditional Japanese prints - is actually impossible. I mean this literally - to make an accurate reproduction is completely impossible.

Perhaps I should try and explain ...

* * *

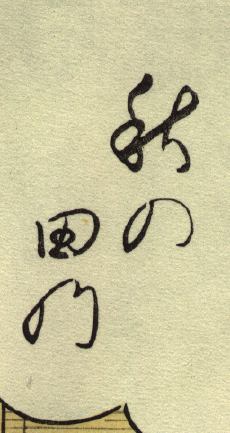

One area where my work has greatly improved over the years is calligraphy carving. Here is an example from 1988 (on the left) compared with one from a few years later (over on the right).

The difference? Aside from the obvious 'chips' here and there in the older work, it is that the curves on the lettering on that one were carved in 'steps', with the knife pausing as it moved around each curve. As the years have gone by, my wrist has become much more flexible and can move around the curves without quite so many jumps and breaks. I have slowly developed the ability to make the lines taper and swell as needed. The lines on the older print look as though they were drawn by a clumsy robot; those on the newer one are carved.

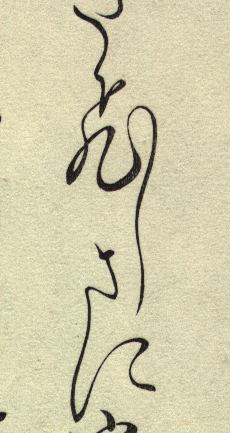

This is a bit of a silly game though ... if one picks very bad prints for comparison anything will look good! Connoisseurs who really know what woodblock prints should be ... they are not fooled by a trick like this. Let's look at a closeup of one of the prints from my first Surimono Album, a design by Shibata Zeshin.

Those small curliques are ... what shall I say - less than elegantly carved. The curves are raw and ragged; they're not much better than the twelve-year old calligraphy sample I just showed you!

Here's a quote from William Ivins, a former curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (speaking here about nineteenth century reproductions of old European woodcuts, but in words that would apply to my own reproductions ...)

"Every line is different - every line is stupid - and the whole character has changed ..."

Aren't I being a bit hard on myself here? Those lines are extremely small; is it really possible for such tiny things to be carved with elegance? Well, if we change the verb tense in that question ... " was it possible for such tiny things be carved with elegance?" ... I can answer it easily: yes!

Take a look at this scan showing an enlarged small portion of a kuchi-e print from the Meiji era, carved by 'just' another one of the innumerable carvers of that era. We have no idea of his name - such things weren't considered important back then. But look at his work - every dot and line in this print is alive!

Take a look at this scan showing an enlarged small portion of a kuchi-e print from the Meiji era, carved by 'just' another one of the innumerable carvers of that era. We have no idea of his name - such things weren't considered important back then. But look at his work - every dot and line in this print is alive!

In defense of myself I have to point out that the old carvers and I have rather different approaches to our work. They started out at a very young age, apprenticed to strict masters, worked long hours seven days a week with time off only for festival days, and pretty much lived their life at the carving bench. My life is of course very different: I print as well as carve, I don't work anywhere near the long hours they did, I have never had a 'master' (strict or otherwise!), and I spread my energies among many other activities ... So of course they were good! Their world was very narrow, but very deep indeed. Mine is the reverse ... wider than they could ever imagine, but as a consequence, quite shallow everywhere.

But this sounds like I am making excuses for poor work, and I'm not going to do that; I've been working on prints for around twenty years now, and even though I spend a lot of time with other projects (the one I'm typing right now for example!), twenty years should count for something! No, my work is not as bad as I am suggesting here ...

I think we have to consider another reason for the difference between my prints and those spectacular old ones. The carver of the original print worked from what was known as the hanshita - a sheet of very thin paper carrying the design and which was pasted onto the block. This hanshita was the 'original' behind every print.

All that was necessary was for the carver to then carve it - seemingly a simple job. But I suggested that this job is actually impossible, and here is what I mean:

Try this experiment - take a pen and a sheet of paper and sign your name. No problem of course, and the pen sweeps and curves smoothly across the surface of the paper. Next take a sheet of thin transparent paper, lay it on top of your signature, and try and make an 'exact reproduction' of what you wrote the first time. It simply cannot be done. You have two choices:

- (a) slowly and carefully guide the pen over each line, trying to make your copy. When you have finished, and inspect the work, you will find that though you may have been 'on the lines' the result looks nothing at all like your signature - it is stiff, wooden and lifeless. "Every line is different - every line is stupid - and the whole character has changed ..."

- (b) now put your pen at the starting point, and quickly 'do' your normal signature again. When you have finished, you will find that although the result now has similar 'life' to the original, the position and details of all the lines has changed.

Faced with these alternatives it would seem that the best way for a carver to approach making a woodblock print from a designer's hanshita would be to take the lesser of the two 'evils' and work in the second method - not worrying too much about the absolute position of each line and dot, but simply trying to carve naturally. The resulting print would vary somewhat from the original design, but it should have the same character.

That sounds like a nice idea ... but there is one very large catch. Go back and play the signature game again, but this time try and make the reproduction of another person's signature! Now which of the two methods will you use? Neither one will work! If you 'stay on the lines' the result is lifeless; if you draw 'freestyle' you lose the individuality of character that was expressed in the original. This is what I mean when I say "... to make an accurate reproduction is completely impossible".

And this, of course, is the situation we traditional carvers face with every stroke and line and dot of every print we make. We must carve those Hokusai lines, Sukenobu lines, Hiroshige lines ... do it as closely to the original as we can, do it with 'life', and yet do it all in such a way that the artist's individuality still comes through! We carvers walk a very fine tightrope with every stroke of the knife, trying to find this balance between 'authenticity' (staying on the lines) and 'character' (carving living lines).

But my story does not end there, because there is one further thing to point out - the Edo and Meiji carvers had something I do not, and can never, have ... they had the original hanshita! All I can see of course, is the print that they carved from the original - I can see their interpretation of the original strokes, but I cannot see the original strokes themselves! My work is thus doubly difficult when compared to theirs ...

In those moments when I am sometimes feeling 'down' about my work, I wonder if I will ever be able to surmount this obstacle and produce truly beautiful prints. Yet at other times, when I enjoy looking through my completed albums of prints, I feel deep pride at seeing how far I have come along this path.

So where do I go from here? Will I ever be able to make 'good' prints? The answer to that question is unknown of course - I must just keep on plugging away. I may feel as though I live in one of Zeno's paradoxes - no matter how closely I approach the 'finish line' I can never cross it - but hey, the journey's the thing ...