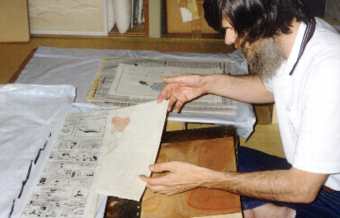

The long days of carving are behind me; days when the sum total of work done was sometimes no more than a few square centimetres on the woodblock. The tiny slivers of wood had been carefully picked out one-by-one from the areas of dense kimono pattern and complex written characters, and the work had gone very slowly indeed ... Towards the end of the carving process the pace had picked up - once all the delicate lines had been cut, the large and wide chisels came into play to remove the waste wood in the open areas of the block, and chips started to fly! But that part had gone very quickly, and then with the carving completed, the workshop was cleaned thoroughly, the printing bench brought out from storage where it sleeps for a few weeks each month, and preparation for printing had begun.

First the barens and brushes had been selected and prepared. The bamboo wrappings of the barens needed replacing after being worn down with the work on the previous print, and some of the brushes needed to be 'touched up' on the sharkskin, to ensure the hair had the proper softness at the tips. The paper also had to be prepared, and this job took quite a bit of time. The large sheets had to be cut one-by-one to the correct size, thus ensuring that the 'watermark' lines in the paper would be truly parallel to the edge of the sheets. One corner of each sheet was then carefully trimmed to a right angle, for use when placing the sheets into the 'kento' marks that are carved on each block. All the sheets were then inspected carefully for tiny flecks of dark mulberry bark. The papermaker Iwano-san and his family go to extraordinary lengths to remove such debris, spending endless hours dipping into freezing cold water to pick out the flecks, but it is inevitable that in a batch of a few hundred sheets of paper, two or three minuscule pieces remain. If such tiny spots fall within unimportant parts of the image it is no problem, but the sheets must all be checked to see that no such spots occur within a face, or other place where they would be immediately noticeable.

Once this was all done, moistening the paper had begun, and this was the 'point of no return'. Once the process has started the paper must remain at a constant level of moisture right until the end of the printing, and as damp washi that has been treated with a gelatin sizing is a perfect breeding ground for molds, producing a batch of prints is a race against time. Once the moistening has begun, nothing must be allowed to interfere with the work; invitations from friends and collectors must be met with "I'm sorry, but the printing has started ... I won't be able to join you today ..."

A wide and soft brush made from goat hair was used to do the moistening - although perhaps 'soaking' would be a better word; sheets of paper were flooded with water two-by-two and were then piled together with moistened newspaper and left to settle overnight. The next morning they were moistened a bit further and carefully stacked in groups ready for printing. After a couple more hours of settling, the printing had begun. That first day's work had not been a long one; the printing of the key block - the sumi - is always the first step, and the paper is then allowed to settle overnight before colours are applied on top of the black outlines. But although it had not been a long day, it had been a difficult day. Perfect printing of the key block is ... well, it is 'key' ... to the success of the print; if the paper is not registered perfectly to the marks it is impossible to print the succeeding colours properly. And this is all the more difficult because the key block must be printed quickly. The wood is constantly on the verge of drying out, and the only way to work is at top speed, pulling impressions one after another, spreading the thin pigment and applying each sheet of paper and rubbing quickly before everything dries. Stop to answer the telephone? Impossible. My local parcel delivery man has learned that when I don't come and answer the door when he knocks, he is just to leave the package in the entranceway ...

So the printing has been under way for a few days - the key block that first evening, and many of the colours on the following two days. The work has gone well and there are now just four impressions left to do. Today will be a day of peaceful and calm work; if I concentrate and don't allow myself to be distracted, the print should be completed by this evening.

Today ... will be a printing day ...

* * *

I get started with the work quite early; because it is Monday, the local swimming pool is closed and I cannot have my usual morning swim ... By 7:30 I am busy with the first block of the day.

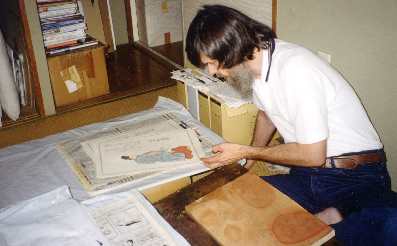

It is the hada iro, the skin colour. On this particular print, three small areas of skin are exposed - face, hand and foot. The pigment brush must thus come down three times onto the block ... swish, swish ... swish, swish ... and again swish, swish ... I then tip my head slightly to one side to inspect each area against the light coming from the window - is there a smooth film of colour on the wood? While I check this, my hand is blindly returning the brush to its place and reaching for the corner of the top sheet of washi on the pile, the one that is peeking out from under its protective cover of moist newsprint. The pigment does look smooth, so I slide out the paper, quickly slip it into the registration marks, and let it fall gently over the block. The left hand reaches out for the baren, again without needing the eyes to help it find the proper place.

As these three areas of colour are widely separated, the baren cannot rub across all three together but must 'fly' across the sheet, only 'touching down' in those places where pigment must be pressed into the paper. Striking the wrong place would result in a permanent blot on the surface of the print. The pressure I apply to the back of the paper must thus constantly vary - from nothing at all here in the space between the face and hand ... right up to a full firmness on each printing area. But because these areas are so small, it is easy to overdo the pressure, or to 'lean' too much on the sharply carved edges of the block. The work looks peaceful and calm, but the concentration must be absolute.

As each sheet is finished, the right hand pulls it off the block and lays it face up on the pile to my right, and then while the left hand reaches out to replace the baren and pick up the pigment applicator I check the sheet - my eyes scanning for missed registration or weak colour impression. OK? Then continue with the next sheet ...

One-by-one, the sheets pass over the block to receive the colour, the pile in front of me steadily decreasing, and the pile of printed sheets off to the side just as steadily growing. During the few moments that each sheet is exposed to the air, it loses a bit of the moisture that it contains, so every couple of minutes the steady rhythm pauses for a moment while I use the goathair brush to spread more water over the covering newsprint to make up for the loss. The printing then resumes. Once the flow of the work has become established I make an estimate of how long this colour will take - I count the seconds to do one sheet ... 45 ..., multiply by 130, the number of sheets in the stack, then add a bit extra for water brushing, etc. It seems like the job should take just about 100 minutes ...

It actually takes a bit longer, and I come to the last sheet in the pile just about twenty past nine. I had to pause for a few minutes partway through the job, as the grain of the wood was starting to become apparent in the impression in the region of the face, and I stopped printing and used a small block of 'nagura' (a type of soft stone used in sharpening ...) to lightly grind the surface of the wood. Although these are woodblock prints that I am making, nobody wants to see woodgrain lines running up through a face.

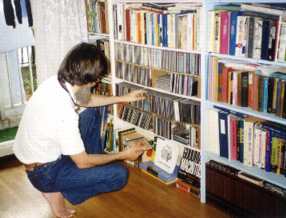

So it's a good start to the day ... only nine thirty, and one of the four colours is already finished. I flip the heavy stack of prints over so that the paper is again face down, and place the pile back on the stand in front of the printing desk, ready for the next colour. But there's no rush to start right away - time to stretch the legs a bit first ... I don't mind sitting in the agura cross-legged position all day, but only if I can get a bit of a break every couple of hours. I move to the kitchen to prepare a cup of tea, and as I do so I pass the dining-room table ... and here are enough distractions to keep me away from the printing bench - if I let them! On top of the pile of papers spread across the desk is the folder with a few notes for the summer issue of the newsletter; this can't be postponed much longer ... Next to that is my notebook with the outline of next year's new print project; I shouldn't be thinking about that until the Hyakunin Isshu series is finished, but of course I am ... Then there is an envelope from a friend in America, containing some designs that he would like me to make into woodblock prints; this too will be a very interesting and attractive project ...

My hand reaches out for one of the files ... but no! Today ... is a printing day! I prepare my mug of tea, and then stop off at my CD shelf on the way back to the workroom. What will be the music to accompany this next printing session? I select a couple of discs and pop one of them into the player before taking my place again on the cushion, making sure that the remote control unit is near to hand. This next colour will be a 'mustard' yellow, overlaying part of the foot to create the straw sandal, and also filling in the wooden frame of the fan this poet is holding. Such small areas of colour are quite easy and quick to print, but do require critical registration; I will have to be extremely careful while inserting the paper into the carved marks.

My hand reaches out for one of the files ... but no! Today ... is a printing day! I prepare my mug of tea, and then stop off at my CD shelf on the way back to the workroom. What will be the music to accompany this next printing session? I select a couple of discs and pop one of them into the player before taking my place again on the cushion, making sure that the remote control unit is near to hand. This next colour will be a 'mustard' yellow, overlaying part of the foot to create the straw sandal, and also filling in the wooden frame of the fan this poet is holding. Such small areas of colour are quite easy and quick to print, but do require critical registration; I will have to be extremely careful while inserting the paper into the carved marks.

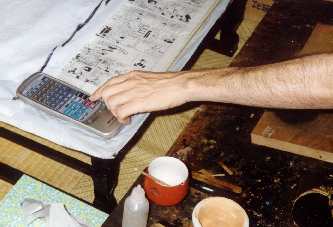

A few minutes later, the familiar rhythm is in swing again ... pigment application, brushing, paper on top, baren, inspection ... Once the pace has settled down, I jab the button on the remote control, and the CD starts to play.

I have the stereo speakers positioned so that they focus exactly onto this cushion, and with extra depth supplied by a bass unit hidden on the other side of the room, I soon lose myself in a world of glorious sound ... and steady work. I have no need this time to calculate how long this colour will take - it truly doesn't matter. Just as before, and just as every time, the pile in front of me steadily decreases, and the pile of printed sheets steadily grows, as one-by-one the prints pass across the block.

But the work does not proceed completely without interruption. Somewhere about half-way through the pile I become aware that the registration is slowly 'creeping' out of alignment. I had also noticed this on the previous colours, but on those woodblocks the registration hadn't been quite so critical and no adjustment had been necessary. It seems that during the key block printing a couple of days ago, the key block had absorbed moisture from the pigment, and had slowly expanded a millimetre or so during the few hours of printing. This expansion of the key block means that the prints in this pile are actually different sizes - 'early' ones are xx millimetres wide, and 'later' ones are xx+'alpha'. There are of course no 'numbers' on the sheets showing me which is which, but I must always be very careful to maintain the proper order - if I were to somehow get them mixed up, correct registration would become impossible. The problem this time is easy to solve; I prepare a tiny wedge of cherry wood, use a chisel to insert it into the wood in the registration mark of this block, and then shave it back just the right amount to ensure that the paper will fall into the correct position on the wood. The next print comes out perfectly registered.

But the work does not proceed completely without interruption. Somewhere about half-way through the pile I become aware that the registration is slowly 'creeping' out of alignment. I had also noticed this on the previous colours, but on those woodblocks the registration hadn't been quite so critical and no adjustment had been necessary. It seems that during the key block printing a couple of days ago, the key block had absorbed moisture from the pigment, and had slowly expanded a millimetre or so during the few hours of printing. This expansion of the key block means that the prints in this pile are actually different sizes - 'early' ones are xx millimetres wide, and 'later' ones are xx+'alpha'. There are of course no 'numbers' on the sheets showing me which is which, but I must always be very careful to maintain the proper order - if I were to somehow get them mixed up, correct registration would become impossible. The problem this time is easy to solve; I prepare a tiny wedge of cherry wood, use a chisel to insert it into the wood in the registration mark of this block, and then shave it back just the right amount to ensure that the paper will fall into the correct position on the wood. The next print comes out perfectly registered.

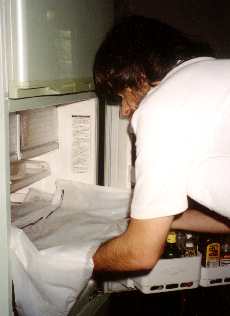

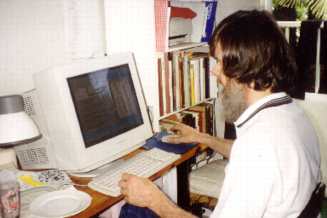

This colour is done on the 130 sheets even before the left-over tea in my mug has completely cooled. It is now just before eleven o'clock, and it's time for a decision - is there enough time before lunch to do another colour, or should I wrap up the paper for a while and turn to another job? Although I had promised myself that I would focus on printing today, there is another job that must be done. Once this print is finished, dried, checked and signed, my assistant Mrs. Ichikawa, who does the wrapping and shipping, will be coming to pick it up, and she will also be expecting to pick up the essay that must accompany it. I wrote this a couple of days ago, sending it out to Mrs. Doi for translation, and her finished work is now sitting beside my computer waiting for me to type it in. I'm a bit of a clumsy typist in Japanese, so that will fill the time until lunch just nicely. I wrap up the stack of printing paper and newsprint, carefully slide it back into the empty shelf in my refrigerator where it 'lives' between working sessions (in the warm months), and start the typing work.

This colour is done on the 130 sheets even before the left-over tea in my mug has completely cooled. It is now just before eleven o'clock, and it's time for a decision - is there enough time before lunch to do another colour, or should I wrap up the paper for a while and turn to another job? Although I had promised myself that I would focus on printing today, there is another job that must be done. Once this print is finished, dried, checked and signed, my assistant Mrs. Ichikawa, who does the wrapping and shipping, will be coming to pick it up, and she will also be expecting to pick up the essay that must accompany it. I wrote this a couple of days ago, sending it out to Mrs. Doi for translation, and her finished work is now sitting beside my computer waiting for me to type it in. I'm a bit of a clumsy typist in Japanese, so that will fill the time until lunch just nicely. I wrap up the stack of printing paper and newsprint, carefully slide it back into the empty shelf in my refrigerator where it 'lives' between working sessions (in the warm months), and start the typing work.

This is fun. If I was attending a school to learn Japanese, and having to really 'study' all the kanji characters and then write tests on them, I think it would not be so enjoyable, but because I do this completely on my own interest there is no stress at all. I have a good dictionary, and whenever I come across a character or compound that I can't read, I look up the pronunciation and then type it in. I find myself looking up the same characters time and time again, sometimes even just a few minutes apart, but as the years go by I am slowly building up skill at recognizing them. Can I really 'read' Japanese? Well, if you give me the newspaper and ask me to read aloud a story on economic or political matters, I certainly won't get very far before breaking down, but if you ask me to read my own newsletter ... Well, of course in that case I can do better. Considering that I'm allergic to 'studying' I guess I'm not doing too badly ...

And of course the little essay is not a complicated piece of writing. The typing is done by noon, and I send off copies by email to a couple of people for checking and correction. Then it's time for lunch! Today, as on many days, this means a trip across the street to Cho-san the baker, where I can not only pick up something tasty for lunch, but can get a glimpse of last month's print hanging up on the wall (they are collecting the entire series, and always display the most recent one in the shop ...)

Back at home, I get another cup of tea and then take my lunch and sit down at the computer again. Perhaps many of you think this is not a very 'nice' thing for somebody to do - to eat lunch sitting at a computer screen, while reading and answering email - and of course if I was living here with other people this would be unacceptable, but in my case it has a major benefit; it forces me to relax and eat more slowly. If I simply sit at a table with a meal ... chomp chomp ... and it's gone in a couple of minutes. Here at the screen though, my hands and eyes are busy with answering the mail, and the meal passes at a much more leisurely pace. Impolite it may be ... but it is much more healthy ...

The mailbox is a mixed bag; first there is a note from somebody who has been browsing my internet web site, and is writing with their comments; I reply with a short note thanking them for letting me know that they enjoyed it. Next are a couple of notices from a mailing list to which I subscribe, which sends out information on new music that is becoming available; I scan these lightly, but find nothing of particular interest and so 'delete' them. Next is a letter from a printmaker friend letting me know about a new internet web site he has seen that has some interesting prints. I use my computer to follow his 'link' and browse through the prints, which are very interesting, and then it is my turn to start writing a letter just like the one I received a few minutes before. 'I have just been looking at your interesting web pages, and enjoyed your prints very much ...' It only takes a couple of minutes to write and then with a quick jab on the 'Send' button, out it goes. It will be at its destination before my lunch is finished - perhaps that other printmaker will read it while eating his lunch. Or dinner maybe - with people scattered around the world, living in different time zones and turning on their computers at different times of day, it sometimes becomes very confusing as to just 'what time it is' ...

And then all that is left in the mailbox - I always save the best for the last - is a batch of postings from my own internet mailing list - the [Baren] Discussion Forum for Woodblock Printmaking. I started this forum late last year to provide a place for printmakers like myself and anybody with an interest in this craft, to exchange information and ideas. At present, there are 42 members, in Japan, Canada, America, England, and Australia. Any message sent out by one of the members is automatically sent to the mailboxes of all the other members, so it is easy to have 'round-table' discussions about our favourite topic - making woodblock prints!

Today's forum messages include a query from one of the members about where to find a particular kind of wood he wants, and I start to type a reply, but then notice that one of the other members has already answered it while I was working this morning. The other messages in the batch are all discussing some new prints that one of the members posted on his own web site. He has developed his own way of carving, by using razors and needles instead of 'regular' carving tools, and has been explaining to everybody just how he does it. I don't think I'll be trying these techniques myself, but it is very interesting to see what he does, and to look at the images of his attractive prints. I enjoy reading all the postings, but don't type a new message for the group; they know I'm in the middle of printing, and don't expect to hear from me for a couple of days.

And so the lunch hour passes - a mix of tasty bread and enjoyable communication with friends around the world. Then of course, it's time to get back to work. I shouldn't forget ... today is a printing day!

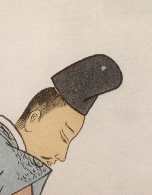

The next block to be done is the smooth deep grey colour of the poet's headgear. This one doesn't pose any large problems, but again the registration is critical. If the 'kento' is misplaced by even the smallest margin, there will be an unsightly gap between his hair and the hat, and the print would be spoiled. For the previous block, the small areas of yellow, I had used a relatively weak and quite flat baren, but I now switch to a stronger one which has a slight curve on the bottom face. If I were to use a flat baren on this block, the edges around the hat would receive too much pressure, and would come out darker than the interior. Using a curved baren allows me to keep the pressure constant over the entire printing area - the colour will be smooth.

After getting the pigment mixed and trying a few tests on a scrap of paper, I get the washi out of the refrigerator and start work. It only takes a few sheets before the pace is established, and once it is, I reach out again for the remote control unit ... This time I don't press the 'Play CD' button, but rather select the cable radio system. It's 1:00 here in Tokyo, which means 11:00 pm in Washington, and there is a program on National Public Radio that I like to listen to at this time on Mondays, a digest of the previous week's interesting programs from that station. During the weeks that I am carving, listening to the radio doesn't pose any problems at all, as carving is usually a very quiet job, but when I am printing, the noise of the baren moving across the back of the paper is sometimes loud enough to drown out the sound of voices on the radio. But on this small colour block that I am printing there is almost no sound from the baren, and I settle down to listen to the radio while the sheets pass in front of me one-by-one.

After getting the pigment mixed and trying a few tests on a scrap of paper, I get the washi out of the refrigerator and start work. It only takes a few sheets before the pace is established, and once it is, I reach out again for the remote control unit ... This time I don't press the 'Play CD' button, but rather select the cable radio system. It's 1:00 here in Tokyo, which means 11:00 pm in Washington, and there is a program on National Public Radio that I like to listen to at this time on Mondays, a digest of the previous week's interesting programs from that station. During the weeks that I am carving, listening to the radio doesn't pose any problems at all, as carving is usually a very quiet job, but when I am printing, the noise of the baren moving across the back of the paper is sometimes loud enough to drown out the sound of voices on the radio. But on this small colour block that I am printing there is almost no sound from the baren, and I settle down to listen to the radio while the sheets pass in front of me one-by-one.

There are no problems with this colour; I watch carefully when the half-way point comes, to catch the best time to adjust the registration marks, and then make the simple adjustment. A short time after that though, I notice something that makes me put down the tools for a moment and inspect the print closely.

There in the centre of the freshly printed hat on the print, is a small white mark - it seems as though the pigment hasn't adhered properly to the paper at that point. When I look back at the block, I see that something is stuck to the wood; it is a tiny scrap of wood, almost certainly a scrap I cut when making the kento adjustment a few minutes ago. It seems that I was a bit careless when blowing away the shavings; one tiny piece found its way onto the surface of the wood, and I failed to notice it when I was checking the pigment on the block before putting the paper on. I clean the scrap off the block before starting the next sheet, but there is no way to repair the damage to the print - this sheet will have to be discarded. But not discarded right now - only at the end of the printing. If 'problem' sheets like this are removed or switched around from their ordained position in the stack of paper, the carefully preserved order and continuity of the stack will be disturbed, and registration adjustment will become awkward. Decisions on what to keep and what to discard must be made only after the entire process is finished. A moment later printing is underway again and the incident is forgotten.

There in the centre of the freshly printed hat on the print, is a small white mark - it seems as though the pigment hasn't adhered properly to the paper at that point. When I look back at the block, I see that something is stuck to the wood; it is a tiny scrap of wood, almost certainly a scrap I cut when making the kento adjustment a few minutes ago. It seems that I was a bit careless when blowing away the shavings; one tiny piece found its way onto the surface of the wood, and I failed to notice it when I was checking the pigment on the block before putting the paper on. I clean the scrap off the block before starting the next sheet, but there is no way to repair the damage to the print - this sheet will have to be discarded. But not discarded right now - only at the end of the printing. If 'problem' sheets like this are removed or switched around from their ordained position in the stack of paper, the carefully preserved order and continuity of the stack will be disturbed, and registration adjustment will become awkward. Decisions on what to keep and what to discard must be made only after the entire process is finished. A moment later printing is underway again and the incident is forgotten.

The radio program comes to an end while I am still quite a long way from the end of the stack and I switch the channel over to the BBC in London. It's only 5:00 in the morning there, but they broadcast 24 hours a day, knowing that they have listeners all over the world. I hear a short general news program, and it is interesting to compare the announcer's very formal 'British English' accent with that of the Americans I had been listening to a few minutes earlier. The news program is followed by their weekly drama program, but I don't want to listen to this now - not while I'm printing. A drama broadcast involves the listener too much, and there is no way that I can concentrate properly on the work while such a program is on ... I flip it over to a music program ...

The stack in front of me slowly shrinks in size, and soon I come to the bottom. I always know when I am getting near the end because by this time in the process, after going through the stack nearly a dozen times, I have come to recognize many of the individual sheets - the one that is third from the end for example, has a particular kink in the paper in a certain place, and when it comes out and onto the block I know that I must be nearly finished ... I don't want to try and make you believe that I've memorized the appearance of 130 basically identical sheets of paper, but quite a number of them do have small 'quirks', and the printer soon learns to recognize these; it gives him a good sense of just where he is in the stack.

And then, with the hat finished, there is a small decision to make; the final colour block that I prepared is for a tiny area that covers this poet's 'belt', smaller than a square centimetre in size. This area has already received colour from the block that printed the main kimono colour, and I originally prepared this extra block planning to do a 'double impression' of that particular area - using the same colour for a second time to give it some body and depth. But the area is so small, and is buried among the complex kimono patterns ... will anybody even notice if I do this? I doubt it very much. Perhaps I should just leave that block out and call this print 'done'. Nobody will ever know ...

After flipping the stack of paper over and replacing it in front of me, I do a 'test print' on one sheet. That small area of slightly deeper blue does look kind of attractive - it's a nice touch. And I sort of like the idea that probably nobody will ever notice it ... only I will know it is there ... So I put aside thoughts of omitting it, and settle back for another hour or so of peaceful work. This one is easy - it is so small that just a tiny swirl of the brush deposits enough pigment, and a quick 'zip zip' with the baren takes the impression. But keeping the registration aligned is still critical, and if I start to get careless now I may spoil the results of many previous hours' work. So the sheets come across the block one-by-one at the same steady pace as the minutes tick by, each one getting a careful inspection.

And then finally, about 45 minutes later, I see again my 'friend' - the sheet with the little kink - and realize that I have come to the end. When the final sheet is done a minute later, I leave it sitting there on top of the pile and study it for a few minutes. It seems 'not bad'. This month's print is certainly not spectacular in any way, but is a quiet and pleasing design. The colours I mixed seem to work together well, and all-in-all I guess I'm pleased with it.

My legs are telling me in no uncertain terms that it's time for a break, so I wrap up the paper, slip it back into the refrigerator again, and start to clean up the pigment pots and brushes, taking them to the sink for washing. The woodblocks too, get a good scrubbing under running water to remove the excess pigment that surrounds each carved area, and are then left leaning against the wall in the workroom, where they will slowly dry out over the next couple of days before being carefully wrapped up for storage. Each time I put away a set of blocks like this, I try and think about when they will be pulled out again for more printing. This cherry wood is quite hard, and a short print run of 130 copies is nothing more than a warm-up for this wood; these blocks are capable of making many many more beautiful prints. Some modern printmakers decide to 'limit' the editions of their prints, and then destroy the blocks after printing is finished, but I will never do that. The whole purpose of making a print is to try and make the image available to as many people as possible, and I certainly hope that these blocks can be used again. Perhaps at the final exhibition of this series next January, if there is enough interest from people who wish to order the series, I will consider another print run. But I don't think I'll print that myself - I want to move forward onto a new project; I don't want to start again from the beginning printing these same blocks again. If another edition of this series is to be made, it will be by another printer - some of the professional printers still living in Shitamachi would be very pleased to be asked to make some of these prints.

My legs are telling me in no uncertain terms that it's time for a break, so I wrap up the paper, slip it back into the refrigerator again, and start to clean up the pigment pots and brushes, taking them to the sink for washing. The woodblocks too, get a good scrubbing under running water to remove the excess pigment that surrounds each carved area, and are then left leaning against the wall in the workroom, where they will slowly dry out over the next couple of days before being carefully wrapped up for storage. Each time I put away a set of blocks like this, I try and think about when they will be pulled out again for more printing. This cherry wood is quite hard, and a short print run of 130 copies is nothing more than a warm-up for this wood; these blocks are capable of making many many more beautiful prints. Some modern printmakers decide to 'limit' the editions of their prints, and then destroy the blocks after printing is finished, but I will never do that. The whole purpose of making a print is to try and make the image available to as many people as possible, and I certainly hope that these blocks can be used again. Perhaps at the final exhibition of this series next January, if there is enough interest from people who wish to order the series, I will consider another print run. But I don't think I'll print that myself - I want to move forward onto a new project; I don't want to start again from the beginning printing these same blocks again. If another edition of this series is to be made, it will be by another printer - some of the professional printers still living in Shitamachi would be very pleased to be asked to make some of these prints.

That would actually be very interesting for me. If I decide to send these blocks out for printing that way, I think the resulting prints will turn out to be quite interesting, as those men have much more experience than I at creating attractive colour combinations. But such decisions will have to wait until next year. For now, for this month anyway, my printing work is done. Tomorrow, after the colours have had a bit of time to settle properly and I have embossed my name on the prints, I will dry them out carefully, inspect them to pull out any spoiled copies, and sign them. I will then call Ichikawa-san to come and pick them up, and away they will go ... out into the world, to the waiting collectors. Where they will end up, nobody knows. Of course I know where they are all going right now, out to the collectors who are supporting this project, but as the years go by, as families move and change, who can say what will happen to them? Some will be passed down through the family, some will be sold, some will be destroyed by fire or earthquake ...

And hundreds of years from now, in a time and place that I cannot even imagine at this moment, someone will open a folder and pick up one of the prints that I made this very afternoon. Pick it up and read on the bottom ... Carving/Printing - David Bull. But of course he will have no idea what those words mean - of the story behind them. But you and I know ...

Today ... was a printing day!