Mr. Kenji Seki

I've been writing these 'Visit to a Craftsman' stories for

many years now, and sometimes when I have been preparing for

the visit, I have thought "Actually, I don't even really need

to go and visit this man - I know what I'll be seeing and

hearing; I can just stay home to write the story ..." And

perhaps you readers have had the same feeling - once you've

seen the title and introduction to a story, you pretty well

know what is coming up.

But of course, I don't do it that way; I always make the

visits before writing these pieces - and this time especially,

I'm glad that I did. Let me set the scene for you: I visited

the woodblock printer Mr. Kenji Seki, to find out how he got

started in this field, and to talk about his time as an

apprentice. Do you think you can imagine the rest of the story?

Well, let's see how close you come!

* * *

Of course, I headed for Shitamachi, home of traditional

woodblock craftsmen for hundreds of years ... Oops! Seki-san

lives in the Tokyo suburb of Hachioji, in a modern house in a

modern housing development. Once welcomed into his home, I

stepped into the tatami-matted work shop ... Oops! No tatami!

Seki-san works in a wooden-floored western-style room. There in

the room was the low printer's bench ... Oops! Seki-san works

standing up at a high western-style workbench! There on the

work surface are the cherry blocks for a reproduction of an old

Ukiyo-e print, carved by one of the old 'hori-shi' ... Oops!

These blocks are plywood - the picture is a modern landscape -

and the carver was ... Seki-san!

There is no room for us to sit and talk in this tiny

workroom, so we sit in the modern living room downstairs for

our conversation. I have a million questions for him - and not

just for this newsletter story. Hidden away inside my bag are

my baren and some prints ... I also have some questions to ask

him about my own printing work. Will I get a chance today?

But the first question must obviously be about these new

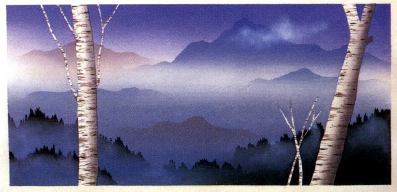

'original' prints he is making; what is going on? He shows us a

few of them - landscape scenes drawn without strong outlines,

in a 'misty' and dreamy mood. They are quite large, and are

presumably meant to become decorative accessories in a modern

style home. It turns out that there are a couple of reasons why

Seki-san has turned to such work: if he simply sits by the

telephone waiting for print publishers to call, he may be

waiting for a long time; woodblock prints are a 'luxury' item,

and in the current economic climate prints do not figure large

in many peoples' minds. There is very little work available in

the traditional field at the moment.

As we talk to him about these pictures though, it becomes

evident that another factor is at work here - he is very much

enjoying himself in the creation of these prints. Although he

was trained as a 'suri-shi' (a print craftsman) to simply print

and print whatever was sent across his desk by the publishers -

without having any opinions on the work at all - it seems that

during all these years he has been watching and studying the

prints under his baren, and has absorbed enough by doing so to

now allow him to move one step further back up the chain, to

design his own works.

That skill is allowing him to adapt to this new world. It

seems that it's time for us to discard much of what we think we

know about these craftsmen, and start building a new image in

our minds. The Heisei era is now nearly ten years old, and the

wide changes taking place in Japanese society are indeed

touching every corner of the land ...

After some discussion about these things, I remember that

I'm supposed to be here to talk about his apprentice years, so

we ask him some questions about this to hear what he has to say

about those difficult days:

"When you started, you were only 14 years old. I guess you

had to do all the 'grunge' work for everybody else, right?

Grinding the pigments for hours, cutting all the paper ..."

"No, not at all. All the men always did those

jobs for themselves. They were 'shokunin'."

"Well, you must have been the one who had to do all the

boring jobs ... rubbing all the brushes on the sharkskin ..."

"No, no. I did my brushes of course, but

everybody else did their own, even the master. They were

shokunin."

By now in the interview, I was starting to feel a bit

frustrated. Were all my ideas about Seki san's life to be

completely upside-down? "Well then, tell us about the first

printing jobs you had to do, you know, the simple stuff like

printing wrapping paper ..."

"Oh, that's not the sort of thing I started

with. My master had the idea that I could do 'easy stuff'

anytime; if I learned the trade by starting with difficult

jobs, I would then be able to handle any work that came

along. The very first job that was given me was to make 100

copies of a difficult multi-coloured print. Of course, I

made a complete mess of it. Nobody told me what to do, how

to do it ..."

What happened to those 100 prints?

"Once I had finished the job, the master looked

at them, took a knife, and simply cut the whole stack in

half. I was then given my next assignment - another very

complex print. I saw all those sheets of beautiful 'washi'

being thrown away and I tell you, I learned fast!"

Didn't they start to give you some instructions?

"No. Nobody told me anything during the entire

ten years that I was there. I just had to watch and figure

it all out on my own. You can't learn something just by

asking questions - your hands have to learn by

themselves!"

I hear this and think of my baren sitting in my bag ... I

guess it's not a good moment to bring it out ...

"What kind of pay did you get in those days? Just a few

hundred yen a month, right?" I am astonished at his answer:

"Yeah, that's right. I got 500 yen a month. And

we had two days off, the 1st and 15th of every month."

At last! Something that matches my preconceptions! I eagerly

press ahead. "So those two days must have been real 'freedom'

for you - going to the movies, taking your girlfriend out ..."

"No way. I was too busy in the workshop - taking

care of my brushes, trying to learn how to make a baren ...

And besides, I had to save up my money so I could buy tools.

The other guys lent me some of theirs at first, but those

had to be returned. I had to buy all my own stuff."

"It sounds like it must sometimes have been a pretty

frustrating time. Were you glad after the years of training

when your master finally said you were ready to be an

independent shokunin?"

"Well ... He was a pretty strong-willed guy, and

I guess I'm also fairly strong-willed ... It didn't end up

quite so neatly as that. One day, after about ten years,

there I was out on the street. I had to start from zero. But

boy, could I print! I could do any job that anyone cared to

throw at me. I could print anything!"

And his big smile tells its own story ...

Maybe this is the right moment ... I open my bag and bring

out my baren. I have been having a bit of trouble with the

final step of the 'wrapping' job - keeping the bamboo skin held

tightly around the inner coil. After years of practice, I've

pretty much got the bamboo folding part figured out, but find

that the cord holding the skin in place somehow always works

its way loose when I start printing. Seki-san picks it up and

says immediately

"The cord is too loose - you can't use a baren

like this!"

I nod in agreement and shrug my shoulders helplessly.

And then suddenly, in a burst of motion ... flip, twist,

loop, tug, tie ... It takes but a moment for him to retie the

cord and pass the baren back to me. Tight as can be. Wonderful!

But it was like watching a magic show on TV; I saw nothing -

just a blur of fingers!

"How did you do that?"

He just smiles. I get the message - you can't learn

something just by asking questions - your hands have to learn

by themselves ...

He and his wife are very friendly to us, and the

conversation rolls along for nearly four hours. But it gets

late, and Sadako and I reluctantly bring things to a close, say

our 'thank you', and start to pack up our things. But as we do,

I have a flash of inspiration, and take out of my bag a folder

of my prints. I pull out one that I made last year, one in

which I used the 'karazuri' ('empty printing' - embossing)

technique. But I don't really know the traditional techniques

well, so I have sort of invented my own way of doing this. The

result is attractive, but a little different from typical

karazuri. I pass it to Seki-san for his inspection. He looks

closely at it, and yes, just as I had hoped, a moment later

comes the question ...

"How did you do that?"

I smile ... and I smile ... and I smile!