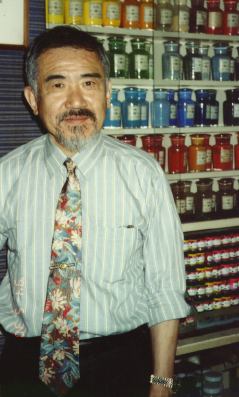

Mr. Kazuyuki Matsuyoshi, pigment

supplier

I was looking forward to my visit this time, out

gathering information for my 'Hyaku-nin Issho' newsletter, because it

took me to my favourite part of Tokyo, an area to which I return time

and time again, whenever I have a chance. No, not Asakusa, where many

of the woodblock craftsmen live and work, although of course I also

love going there, but this time to the Kanda and Jimbocho district.

It's that stretch of Yasukuni-dori from Kudanshita along to

Ogawamachi that is the magnet for me ... the dozens and dozens of

second-hand bookshops all in a long row. Usually, once I get started

browsing through these shops, I can pretty much forget about getting

anything else done for the rest of the day, but this time, when I

came out from the Jimbocho subway station and headed eastwards, I had

to steel myself to walk right by all the beckoning mountains of

books. Today's mission was different, a visit to the shop of Mr.

Kazuyuki Matsuyoshi, dealer in pigments of every description, and the

place where I obtain the ganryo, the colours with which I

make my prints.

Not too

long ago, I would have found his store in an old brown wooden

building, but the pressure from the real estate developers put an end

to that, and the shop now occupies the ground floor space in a tall

modern building. Similar steel and concrete buildings crowd around on

both sides, as the old wooden buildings of this block, which narrowly

escaped the fires during the war, have all since fallen to less

dramatic, but just as effective, forms of destruction. But once

inside the shop, such thoughts become irrelevant, as one is

surrounded by shelf after shelf, row upon row, of jars of coloured

pigments ... stacked from floor to ceiling, up far higher than I can

reach. You would like some green pigment? On a few shelves just

inside the door stand 92 jars of green, each one different from its

neighbour. How about some yellow? More than 50 choices. What about

some white? What choice can there be for white? But here I see more

than four dozen different white shades standing ready for your

choice! And these are all just one particular type of pigment.

Similar selection of other types surround on every side. Here on Mr.

Matsuyoshi's shelves, and down in his storerooms, are hundreds and

thousands of different pigments, made from materials from all parts

of the world, waiting for use by all types of artists.

Not too

long ago, I would have found his store in an old brown wooden

building, but the pressure from the real estate developers put an end

to that, and the shop now occupies the ground floor space in a tall

modern building. Similar steel and concrete buildings crowd around on

both sides, as the old wooden buildings of this block, which narrowly

escaped the fires during the war, have all since fallen to less

dramatic, but just as effective, forms of destruction. But once

inside the shop, such thoughts become irrelevant, as one is

surrounded by shelf after shelf, row upon row, of jars of coloured

pigments ... stacked from floor to ceiling, up far higher than I can

reach. You would like some green pigment? On a few shelves just

inside the door stand 92 jars of green, each one different from its

neighbour. How about some yellow? More than 50 choices. What about

some white? What choice can there be for white? But here I see more

than four dozen different white shades standing ready for your

choice! And these are all just one particular type of pigment.

Similar selection of other types surround on every side. Here on Mr.

Matsuyoshi's shelves, and down in his storerooms, are hundreds and

thousands of different pigments, made from materials from all parts

of the world, waiting for use by all types of artists.

The shop has been here for about 60 years, and was

set up by Mr. Matsuyoshi's father, originally as an offshoot of a

family business in Kyoto. I had guessed that it would have been a

desire to be near artists and book publishers that led him to choose

this area for his business, but it seems that this was not the case.

Rather it was the proximity to businesses involved in making

clothing, who needed various dyes and pigments, and who were once

common in this area, that dictated the choice. Times have changed

though, and Mr. Matsuyoshi's clientele is no longer purely 'local' in

scope. It now includes not only people working with fabric dyeing,

but woodblock printmakers like myself, 'kamban' (sign) designers, and

of course the Japanese 'nihonga' painters for whom those 92 jars of

green are waiting ... His customers are found all over Japan, and the

shop even makes some shipments overseas, although Matsuyoshi-san

admits that unless he improves his English, this will necessarily

remain a minor part of his business ...

There have been some exciting times.

Matsuyoshi-san was only a young boy, and thus shipped out to the

countryside during the wartime years, but he certainly remembers the

time about fifteen years ago when they had a disastrous fire in their

storehouse. He has vivid memories of the firemen coming out of the

building in their 'new' multi-coloured uniforms. Spraying water over

mountains of coloured pigments may seem funny in retrospect, but the

clouds of smoke coming from burning toxic materials was probably

anything but funny at the time ...

Most of

the products in the shop are now sold in a prepared 'ready-to-use'

form, but a small row of jars across the top of a cabinet gives

testimony as to how the business has changed down the years. In these

jars is a collection of some of the raw materials from which various

traditional colours are made: flower petals, seeds, cones, etc.

Reading the labels ('benibana', 'yamamomo', 'yashiyadama', 'ukon'

...) brings up memories of a vocabulary not often heard nowadays ...

as the dust on the jars can testify. But I should not leave the

impression that this is a dessicated old shop. During the couple of

hours that I sit chatting with Mr. Matsuyoshi, the telephone and fax

work continuously. His assistants wrap and pack a number of large

boxes to be shipped out, and there is a general hum of activity.

Most of

the products in the shop are now sold in a prepared 'ready-to-use'

form, but a small row of jars across the top of a cabinet gives

testimony as to how the business has changed down the years. In these

jars is a collection of some of the raw materials from which various

traditional colours are made: flower petals, seeds, cones, etc.

Reading the labels ('benibana', 'yamamomo', 'yashiyadama', 'ukon'

...) brings up memories of a vocabulary not often heard nowadays ...

as the dust on the jars can testify. But I should not leave the

impression that this is a dessicated old shop. During the couple of

hours that I sit chatting with Mr. Matsuyoshi, the telephone and fax

work continuously. His assistants wrap and pack a number of large

boxes to be shipped out, and there is a general hum of activity.

I am not a very good customer of this shop, as I

don't make very many prints, and each small packet of inexpensive

pigment that I buy lasts me for years on end, but hopefully most of

his clients are more productive than I, and his business will be able

to survive well into the future. I certainly hope so, because it is

an important link in the chain of craftsmen and suppliers without

whom I could not continue my work. But of course, I shouldn't say

that, because all of those links are vital, none more important than

any another. If any one of them were to break, the entire process of

making my prints would come to a halt. Matsuyoshi-san, thank you for

keeping up your business when all around you are giving up and

selling out to those giant sports shops that are taking over your

district. I promise to try and get my nose out of the bookshops, and

come and visit a bit more often!