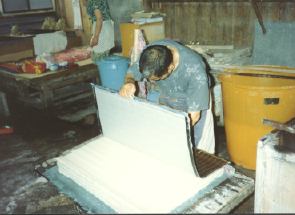

Mr. Kazuo Yamaguchi, paper maker

On one of my visits to Japan about ten years ago, I purchased a woodblock print made a number of years ago by Toshi Yoshida. It depicts a scene in Fukui Prefecture, a large vermillion gate to a shrine in Otaki village. Mr. Yoshida must have sketched the scene on a trip to visit one of the workshops in the town, for this is one of the famous papermaking villages of old Japan. For many hundreds of years the principal occupation of the residents has been the production of traditional Japanese paper, specifically 'Echizen washi', after the Edo-era name of the district.

As my family strolled up the slope through the village one morning late this past August, we found ourselves face-to-face with the scene shown in Mr. Yoshida's print. The basic view hasn't altered much; stone lanterns still guard the approach, and a thatched roof house stands near the large gate, which still straddles the road. The passage of the years is marked by a few changes; the new asphalt road surface, the convenience store visible off to one side, and the trucks roaring through the gateway loaded with bales of paper from the factories which have largely replaced the old workshops.

We had left our hotel quite early, but when we

arrived at the workshop the day's labour was already well under way.

Mr. Kazuo Yamaguchi and his wife Kinuko were busy at their task of

turning tree bark into works of art, glowing sheets of 'washi'. They

were doing the final preparation necessary before the actual work of

'rocking' the paper could begin, Kazuo-san rinsing a pile of kozo

(mulberry) fiber which has just been beaten, and Kinuko-san picking

out unwanted pieces of dark coloured bark.

We had left our hotel quite early, but when we

arrived at the workshop the day's labour was already well under way.

Mr. Kazuo Yamaguchi and his wife Kinuko were busy at their task of

turning tree bark into works of art, glowing sheets of 'washi'. They

were doing the final preparation necessary before the actual work of

'rocking' the paper could begin, Kazuo-san rinsing a pile of kozo

(mulberry) fiber which has just been beaten, and Kinuko-san picking

out unwanted pieces of dark coloured bark.

It was a day just a few months after the end of the war when the 15-year old Kazuo first started work in this room, the seventh generation of his family to train in this craft. He has been here ever since, spending seven days a week bent over his vat of kozo fibers, holding a wide bamboo screen, and dipping and rocking, dipping and rocking, until each sheet of paper takes shape before his eyes. Now, 45 years later, as I stand by his side and watch, I am amazed at the intensity with which he works. As he rocks the screen gently forward and back his eyes are never still, scanning every square inch of the emerging paper surface for imperfections or problems. A casual toss of the wrist sends a lump of fiber flying off the screen. A slightly stronger shaking motion smooths an overly thick area. He is in complete control of the developing sheet.

As the day wears on, the sunlight slants further into the room, illuminating the kozo fibers in the vat and turning the mixture into an iridescent liquid silk, swirled by his dipping motions. The pile of paper grows higher, and by the time he is finished when the sun goes down this evening there will be between 100 and 150 sheets stacked there. Over the next few days these will be drained, squeezed in an ancient press, dried on wide boards, and then finally shipped out to an impatient printmaker somewhere, perhaps in Japan, or perhaps in Canada or Europe, one who has been waiting for the shipment for a long time.

A generation ago this area was crowded with workshops run by people like Yamaguchi-san, but over the years, one by one, they have either switched over to mechanized methods of production using wood pulp, or have closed their doors for lack of new workers willing to take over. These days, young people willing to step into their father's shoes are few and far between, especially when those shoes will spend so much time rooted to one spot, and when the work is so old-fashioned and repetitive. Demand for paper like Yamaguchi-san's is high, but he is forced to turn away customers. There are only so many hours in a day that one man can stand there with his hands in the vat.

Material supply is a problem too. Cultivating and

harvesting the mulberry trees is very labour intensive and basically

unrewarding work, and it is becoming more and more difficult for

Yamaguchi-san to obtain adequate supplies of raw material. Every year

more and more of his suppliers close their doors, and the story is

always the same - there is nobody to take over from the elderly

workers who are retiring. When I get nervous and ask him about future

supply, he laughs and tells me not to worry. He will certainly be

able to make the paper I need to complete my print series over the

next seven or eight years. As for the future ... he simply shrugs his

shoulders.

Material supply is a problem too. Cultivating and

harvesting the mulberry trees is very labour intensive and basically

unrewarding work, and it is becoming more and more difficult for

Yamaguchi-san to obtain adequate supplies of raw material. Every year

more and more of his suppliers close their doors, and the story is

always the same - there is nobody to take over from the elderly

workers who are retiring. When I get nervous and ask him about future

supply, he laughs and tells me not to worry. He will certainly be

able to make the paper I need to complete my print series over the

next seven or eight years. As for the future ... he simply shrugs his

shoulders.

In future issues of this newsletter you will be reading more about the Yamaguchi family. Their washi plays a very important part in my work. It is literally impossible to use any other kind of paper for woodblock printmaking. The repeated full-strength rubbing on the back of each damp sheet during the printing process would utterly destroy any Western paper, and even most weaker Japanese papers. Kozo is the material ... and Yamaguchi-san is the man to put it together. Ever since I have been making prints on his paper, I have sent him a copy of each completed print. I want to make sure that he is fully aware of what an important part he plays. Usually, once his paper leaves his shop, he never sees it again, but I want him to see in his mind, as he stands in front of the vat, the finished product. One of the great pleasures in this project for me is to view the entire process, the bringing together of scraps of tree bark, lumps of iron, clods of coloured earth, scraps of shark skin, sheaves of bamboo leaves .... the list seems endless.

When you receive your next print from me, look along the right hand vertical margin. The characters printed there tell the story: 'paper by Kazuo Yamaguchi'.

Mr. and Mrs. Yamaguchi, for your dedication to

your ancient traditions, thank you very much.

I have been shooting for a schedule of September,

December, March and June for issuing this little newsletter, but I'm

running a bit late this time .... When we went down to the country

this summer, I took along a box filled with books carefully

accumulated over the past year. The idea was to make sure that I had

something to do if I managed to get through all the carving and

writing. I seem to have got my priorities mixed up. By the end of

August, the book box was empty, and the newsletter not even started

....

I have been shooting for a schedule of September,

December, March and June for issuing this little newsletter, but I'm

running a bit late this time .... When we went down to the country

this summer, I took along a box filled with books carefully

accumulated over the past year. The idea was to make sure that I had

something to do if I managed to get through all the carving and

writing. I seem to have got my priorities mixed up. By the end of

August, the book box was empty, and the newsletter not even started

....

Back to the Toyo Bunko to place the order. This

time I spoke directly to the microfilm company representative,

discussed the process with him, and was assured that there would be

no problems. Sounds good. Back to the English classes, and the

waiting ... Waiting for Yamaguchi-san's paper, Shimano-san's blocks,

negatives ...

Back to the Toyo Bunko to place the order. This

time I spoke directly to the microfilm company representative,

discussed the process with him, and was assured that there would be

no problems. Sounds good. Back to the English classes, and the

waiting ... Waiting for Yamaguchi-san's paper, Shimano-san's blocks,

negatives ...

As I sat and talked to Naritsugu Kamata, with his

daughter Akemi-chan busy interrupting to show me all her treasures,

it slowly dawned on me that I was talking to a mirror. I heard him

tell me about his desire to live in the country and build a home, and

to create a lifestyle in which productive work blended with family

life, rather than being arbitrarily separated. I had not heard such

talk from a Japanese before. Of course, we all understand that behind

the rhetoric we read in the newspapers, a Japanese man and a Canadian

man may have pretty much the same goals in life, but I was a bit

surprised to find such a close correspondence.

As I sat and talked to Naritsugu Kamata, with his

daughter Akemi-chan busy interrupting to show me all her treasures,

it slowly dawned on me that I was talking to a mirror. I heard him

tell me about his desire to live in the country and build a home, and

to create a lifestyle in which productive work blended with family

life, rather than being arbitrarily separated. I had not heard such

talk from a Japanese before. Of course, we all understand that behind

the rhetoric we read in the newspapers, a Japanese man and a Canadian

man may have pretty much the same goals in life, but I was a bit

surprised to find such a close correspondence.