Part One

Handmade woodblock prints are one of the favourite

souvenirs taken home by visitors to Japan, and their beautiful

colours and soft fluffy paper have delighted viewers for over three

centuries. Whether it be a print of a geisha from a past age, a

kabuki actor strutting across the stage, or even a more modern image,

the woodblock technique seems to provide the perfect means of

expression to catch the essence of things Japanese.

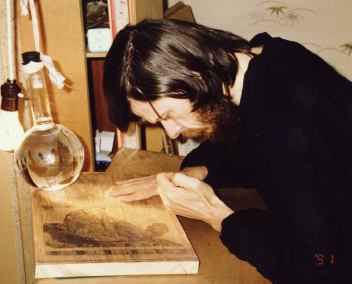

Elementary school students

in Japan all learn to make simple woodblock prints in their art

classes, and many of them keep it up as a hobby when they get older.

The most common type of prints they make are cards for New Year, and

thousands of people around the country keep albums full of hand

printed cards they have received in exchanges with friends or

acquaintances. Art supply stores and community centers set up

displays of such cards each January, and even the Post Office

sponsors a national competition for printmakers to enter.

Elementary school students

in Japan all learn to make simple woodblock prints in their art

classes, and many of them keep it up as a hobby when they get older.

The most common type of prints they make are cards for New Year, and

thousands of people around the country keep albums full of hand

printed cards they have received in exchanges with friends or

acquaintances. Art supply stores and community centers set up

displays of such cards each January, and even the Post Office

sponsors a national competition for printmakers to enter.

Professional printmakers study and train for many

years to reach the top levels of their craft, but as the actual

techniques of making prints are really quite simple, it is possible

for beginners to obtain very satisfying results on their first

attempts. Over the next few weeks or so in this space I will outline

the basic procedures for making simple woodblock prints. I will

include enough information to allow you to actually make your own

prints, starting from scratch and proceeding step-by-step to the

finished product. The same techniques can be used to make not only

prints for framing or collecting, but also personalized greeting

cards for Christmas or New Year, unique name cards (meishi), or

attractive stationery such as letter paper or envelopes. I will cover

selection and preparation of suitable designs, cutting the

woodblocks, doing the actual printing, sources for materials, tools

and instructional materials, and also ideas for other applications of

the woodblock technique.

Only a few, quite

inexpensive tools will be needed. A special work place is not

necessary, and the dining room table (or kotatsu!) will do quite

well. As for artistic ability? Well of course, a budding Hokusai

could no doubt produce stunning designs, but even those of us who are

closer to that elementary school level can make beautiful prints. A

great deal of the beauty seems to lie in the production technique and

the materials themselves, and I can speak from personal experience

that a person with very modest creative abilities can turn out

satisfying work. Like to give it a try? Join me next week, and let's

get started!

Only a few, quite

inexpensive tools will be needed. A special work place is not

necessary, and the dining room table (or kotatsu!) will do quite

well. As for artistic ability? Well of course, a budding Hokusai

could no doubt produce stunning designs, but even those of us who are

closer to that elementary school level can make beautiful prints. A

great deal of the beauty seems to lie in the production technique and

the materials themselves, and I can speak from personal experience

that a person with very modest creative abilities can turn out

satisfying work. Like to give it a try? Join me next week, and let's

get started!

Part Two

Woodblock prints are made by what is known as a

'relief' process. Planks of wood are carved to leave raised areas on

which pigments are brushed. The colours are transferred to paper by

rubbing with a tool known as a 'baren'. The step-by-step instructions

in this series of columns will cover preparation of a design,

transferring it to wood blocks, carving, printing, and

troubleshooting. As space in the column is limited, descriptions will

necessarily be quite concise. Read carefully, and if my instructions

leave you a bit unclear on what to do at any point, don't hesitate,

try .... 0428(22)2212!

When I receive correspondence from Japanese

friends, it is frequently written on handmade paper decorated with

seasonal designs. Use of such paper is very popular in Japan, and I

thought that it might be a good idea for our demonstration of the

woodblock printing process to show how to make some.

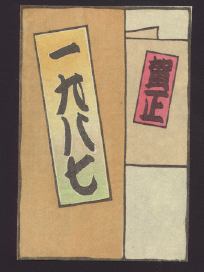

As this is April, and I'm not particularly

imaginative, I will use a simple design of cherry blossoms based on

origami flowers folded by my wife. The pattern will appear in two

opposite corners of the notepaper with the rest remaining blank for

the message. Making the master sketch is the first step, and this

should be drawn the same size as the final print. For your first

printmaking attempt, avoid including many small details in your

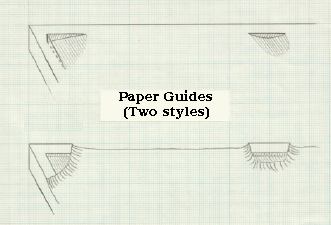

design, and stick to simple masses of colour.  After you have something suitable down on paper

(any handy paper will do), pencil in an outline to show where the

edge of the print will fall, and then about a centimeter outside this

line, mark in the position of two printing paper guides that we will

later carve on each woodblock, an 'L' shape in the lower corner, and

a simple straight line along the bottom edge (see photo). (All

printing will be done with the paper held along its length, and not

'standing up'.)

After you have something suitable down on paper

(any handy paper will do), pencil in an outline to show where the

edge of the print will fall, and then about a centimeter outside this

line, mark in the position of two printing paper guides that we will

later carve on each woodblock, an 'L' shape in the lower corner, and

a simple straight line along the bottom edge (see photo). (All

printing will be done with the paper held along its length, and not

'standing up'.)

My notepaper is to be printed in three colours,

pink blossoms, a yellow highlight, and a green background. Each will

need a separate woodblock, so three tracings must now be prepared to

guide the carving, one for each colour. These tracings are made by

taking pieces of thin paper and pinning them in place over the master

sketch, one at a time. On each one, trace around the outline of all

the areas where that particular colour is to appear, using a fine

point marker. Ignore everything else. 'Shading in' these outlined

areas will make it a bit easier to do the carving later. Also trace

(carefully!) the exact position of those two paper guides. We thus

get a sheet matching one colour that appears in the print. A

complicated woodblock print design can require dozens of these

tracings, but I think that we'll stick with about three for now

...

In next week's column, we'll paste the finished

tracings onto the blank woodblocks and start carving. See you

then!

Part Three

Finished your homework? Colour separation tracings

all ready? Let's get on with the carving!

Before the cutting can begin, the tracings must be

glued onto the woodblocks. Use a standard household paste, spread a

thin layer smoothly over the surface of the block, and then place the

tracing FACE DOWN in position on the wood. (Later, when we are

printing, that paper also will be placed face down to receive the

colour). Smooth out the tracing paper carefully, being sure not to

distort it or stretch it in any direction. Repeat the process on

another block with each tracing (using both sides is OK).

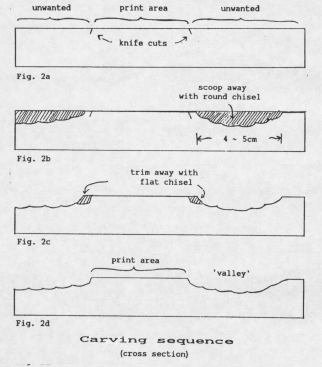

For carving, we will use

three knives from a standard 'school' set, first cutting around the

outlines with the main carving knife ('toh'), next removing wide

unwanted areas with the round chisel ('marunomi'), and finally

trimming away waste close to the printing areas with the small flat

chisel ('aisuki').

For carving, we will use

three knives from a standard 'school' set, first cutting around the

outlines with the main carving knife ('toh'), next removing wide

unwanted areas with the round chisel ('marunomi'), and finally

trimming away waste close to the printing areas with the small flat

chisel ('aisuki').

You can hold the carving

knife either in your fist (giving stronger cutting), or just like a

pencil (giving easier guidance). Cut around the outlines, holding the

knife at an angle that will produce a beveled edge on the final areas

(Fig. 2a). Keep the tip of the blade about 1 ~ 2mm deep in the wood,

and go right around the entire outline of each area. When this is

done, switch to the round chisel, and start gouging away the waste

wood (unshaded portions of each tracing). Only the waste lying within

about 5cm of any printing area will need to be removed. You should

aim to create a 'valley' around each of these areas, with a depth

that varies with the distance (Fig. 2b). Hold the chisel firmly in

one hand, and guide the tip with the fingers of the other, always

being careful to keep your fingers safely behind the cutting edge.

Work with a scooping motion, changing direction as the grain of the

wood dictates. Do not carve right up to the outlines previously cut

with the 'toh', but keep a short distance away.

You can hold the carving

knife either in your fist (giving stronger cutting), or just like a

pencil (giving easier guidance). Cut around the outlines, holding the

knife at an angle that will produce a beveled edge on the final areas

(Fig. 2a). Keep the tip of the blade about 1 ~ 2mm deep in the wood,

and go right around the entire outline of each area. When this is

done, switch to the round chisel, and start gouging away the waste

wood (unshaded portions of each tracing). Only the waste lying within

about 5cm of any printing area will need to be removed. You should

aim to create a 'valley' around each of these areas, with a depth

that varies with the distance (Fig. 2b). Hold the chisel firmly in

one hand, and guide the tip with the fingers of the other, always

being careful to keep your fingers safely behind the cutting edge.

Work with a scooping motion, changing direction as the grain of the

wood dictates. Do not carve right up to the outlines previously cut

with the 'toh', but keep a short distance away.

The last stage is the final trimming with the

small flat chisel. Use it in the same fashion as you did the round

chisel, guiding with your fingers, and carefully pare away the waste

wood right up to the outlines (Fig. 2c).

When the main carving is done, it is time to cut

the two guides on each block for the printing paper. Use the main

carving knife to cut on the lines, and the small flat chisel to clear

away the waste, and make a couple of shallow ledges like those shown

in the next photo. Cutting these ledges will allow the paper to be

positioned in the proper location on each block to allow the colours

to line up perfectly. When this is done, wash the blocks to remove

leftover tracing paper, and get ready to start mixing your colours.

Until next week ....

Part Four

Are you still with me? I hope so, because we're

getting closer to the payoff, and soon you'll see your finished

print!

Before we can start printing, there is a bit of

preparation to do.....

Paper: It is inconceivable

that we would use any paper other than 'washi' (Japanese traditional

paper) for woodblock printmaking. The long fibers provide the

strength necessary to stand up to the beating it gets when being

rubbed onto the blocks, and yet also give it the famous soft fluffy

texture for which it is famous. Many types of washi are suitable for

woodblock work. If you are choosing one in a paper shop, ask the

advice of the clerk, and try to get one not too thick, not too thin.

A 'sized' paper (in Japanese - with 'dosa') is preferable. Two common

woodblock papers are 'hosho' and 'torinoko'.

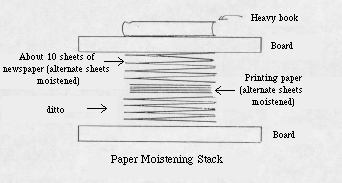

Cut the paper to the

appropriate size for your print, remembering to leave extra margins

for the paper to fit into the guides carved on the woodblocks. (These

margins will be trimmed off after printing.) For your initial

printing attempt, a stack of about 10 sheets should be sufficient for

experimentation. Before the actual printing can begin, the paper must

be moistened. If we tried printing on dry paper, it would expand

unevenly as it absorbed the water from the blocks, and registration

of multiple colours would become impossible. One convenient way to

moisten the paper is to press it between sheets of wet newspaper for

a couple of hours (pros do it the night before). Use a shallow basin

of water and a brush like a wallpaper brush (or wide, clean

paintbrush), dampen alternate sheets of both the printing paper and

the sheets of newspaper, then stack them together as shown in the

picture, and wrap the stack in a plastic garbage bag until the

moisture has equalized. What level of dampness are we aiming for? The

printing paper should end up feeling about like a shirt that has just

come out of the spin drier, ready for hanging on the clothesline.

Make sense?

Cut the paper to the

appropriate size for your print, remembering to leave extra margins

for the paper to fit into the guides carved on the woodblocks. (These

margins will be trimmed off after printing.) For your initial

printing attempt, a stack of about 10 sheets should be sufficient for

experimentation. Before the actual printing can begin, the paper must

be moistened. If we tried printing on dry paper, it would expand

unevenly as it absorbed the water from the blocks, and registration

of multiple colours would become impossible. One convenient way to

moisten the paper is to press it between sheets of wet newspaper for

a couple of hours (pros do it the night before). Use a shallow basin

of water and a brush like a wallpaper brush (or wide, clean

paintbrush), dampen alternate sheets of both the printing paper and

the sheets of newspaper, then stack them together as shown in the

picture, and wrap the stack in a plastic garbage bag until the

moisture has equalized. What level of dampness are we aiming for? The

printing paper should end up feeling about like a shirt that has just

come out of the spin drier, ready for hanging on the clothesline.

Make sense?

While the paper is 'cooking', the other materials

can be prepared.

Paste: Using a paper cup

and an old chopstick, take some white household paste (just like we

used for pasting the tracing on the blocks) and blend it with water

to about the consistency of .... of what? Well, how about - runnier

than face cream, thicker than pancake batter. Make sense?

Pigments: Printmakers use

many types of pigments, but probably the easiest ones for beginners

to handle are standard watercolours from tubes. You can either pick

the colours you want from the selection at the store, or mix your

desired shades using primaries, just like you did back in elementary

school. Whichever way you choose, squirt some of the desired colour

into a saucer or shallow bowl, add water, and mix to about the

consistency of .... of what? This will be up to you. A very watery

mixture will produce a light, delicate colour in the finished print.

Using less water will result in a deeper, stronger colour. You have

complete control, and will have to experiment to find the combination

that suits you. For my sample notepaper, where I wanted a very

delicate tint, I diluted the pigments to about the strength of

tea.

Lay a damp towel under the woodblock so that it

won't slide on the table while you're printing (only very slightly

damp - otherwise the block will warp upwards ...), and lay out your

materials ready for use - pigment bowl with the small paintbrush, cup

of paste with a chopstick, the woodblock printing brush, the baren,

the stack of moistened paper (tucked away inside wet newspapers to

keep it damp), and a basin of water with your moistening brush

standing in it. A few minutes before starting, use this brush to

moisten the surface of the woodblock so that it will be ready to

receive the colour.

So there we are. The preparation is all done, and

next week we'll finally start the actual printing work. See you

then!

Part Five

Welcome back! Colours mixed? Paper moist and

ready? Let's get on with it! Making each colour impression is a

simple step-by-step process. A few minutes before starting printing,

moisten the surface of the block well.

1) Transfer some colour to the woodblock. How

much? Just a moderate smear. Don't try to 'paint' the block, just

move some pigment over there. After seeing the final result, you will

be able to see if you need more or less colour next time.

2) Transfer some paste to the woodblock. How much?

Just a blob hanging from the end of the chopstick (more for wide

areas). Don't be stingy. Without paste, the colour will be weak and

blotchy. Too much doesn't really hurt at all.

3) Mix these together with the main brush. Dig in.

Imagine you're scrubbing the floor with it. The colour and paste must

be spread thoroughly over all the raised portions of the block. Add

more pigment or paste if there doesn't seem to be enough. Don't rub

the brush over those places outside the 'valley' we previously carved

around the design areas. The final few strokes should be soft,

gentle, and straight across the block, to smooth out the mixture. If

you position a desk light shining on the work area, you should be

able to see a smooth, glossy layer covering the block. Move on

quickly to the next step (before it starts to dry).

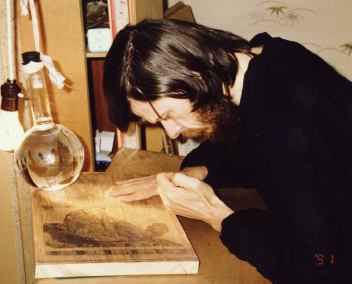

4) Put some paper on the

block. That's easy for me to say! (This is awkward, and I should have

asked you to practice this step before we started.) Slip a sheet out

of the damp newspapers, and hold it face down as in the photo with

the second and third fingers of each hand. No thumbs. Slide the

corner into the 'L' mark carved on the block. Put your thumb down to

lock it in place. Place the other side of the paper against the

straight guide. Put your thumb down to lock it there. Let go with

your fingers, while keeping your thumbs down firmly. When the paper

has fallen smoothly onto the wet block, lift your thumbs off gently,

trying not to disturb the position of the paper. Move right along

....

4) Put some paper on the

block. That's easy for me to say! (This is awkward, and I should have

asked you to practice this step before we started.) Slip a sheet out

of the damp newspapers, and hold it face down as in the photo with

the second and third fingers of each hand. No thumbs. Slide the

corner into the 'L' mark carved on the block. Put your thumb down to

lock it in place. Place the other side of the paper against the

straight guide. Put your thumb down to lock it there. Let go with

your fingers, while keeping your thumbs down firmly. When the paper

has fallen smoothly onto the wet block, lift your thumbs off gently,

trying not to disturb the position of the paper. Move right along

....

5) Grasp the baren, and

rub the back of the paper to create the impression. How hard to

press? Harder than you think. This is tough paper, even if it is wet,

and you are trying to press the pigment right into it. Apply pressure

with the heel of your hand, rather than through your fingers (see

photo). Rub in a side-to-side motion at first, and then in a circular

pattern. Cover all the necessary areas, and only those areas. Rubbing

where the 'valley' is carved will leave you with blotches in unwanted

areas. It should be done in a few seconds. If the paper is thin,

pressure should be lighter, but a thick paper will need real grinding

away at it. If necessary, the baren can be lubricated with a drop or

two of camellia oil to help it slide.

5) Grasp the baren, and

rub the back of the paper to create the impression. How hard to

press? Harder than you think. This is tough paper, even if it is wet,

and you are trying to press the pigment right into it. Apply pressure

with the heel of your hand, rather than through your fingers (see

photo). Rub in a side-to-side motion at first, and then in a circular

pattern. Cover all the necessary areas, and only those areas. Rubbing

where the 'valley' is carved will leave you with blotches in unwanted

areas. It should be done in a few seconds. If the paper is thin,

pressure should be lighter, but a thick paper will need real grinding

away at it. If necessary, the baren can be lubricated with a drop or

two of camellia oil to help it slide.

6) Peel off the paper with a quick motion, inspect

your work, and slip it back under the newspaper where it will remain

moist until the next colour. If you've prepared, say 10 sheets,

repeat this process on all 10, making adjustments as necessary

depending on the results (more/less pigment, longer/harder rubbing,

more careful brushing, etc.). When done with the 10, change the

block, and move on to the next colour. And so on until you're

finished....

There's more to discuss, but we're about out of

space this week. I'll cover some further aspects of the printing

procedure in our wrap-up column next week. But go ahead, don't wait

for me. Get busy!

Part Six

Hello again, and how did you make out with your

printing during the week? What, you had problems?

Is the impression uneven, no colour in some areas?

Perhaps you:

- waited too long before getting the paper on

the block, and the pigment dried in place.

- didn't brush the pigment thoroughly over the

entire area.

- didn't use enough pigment and paste.

- didn't rub firmly enough with the

baren.

- missed some areas with the baren.

- don't have enough moisture in the

paper.

The colour is not smooth, but 'watery'. Perhaps

you:

- didn't use enough paste.

- have just too much water in the pigment

mixture.

- have too much moisture in the paper.

Smears of colour show in unwanted areas (different

every time). Perhaps you:

- pressed the baren into that valley surrounding

the coloured areas. (try and keep it absolutely horizontal)

Smears of colour show in unwanted areas (similar

each time). Perhaps you:

- didn't carve those unneeded areas deep

enough.

Different colours don't 'register' properly.

Perhaps you:

- are not getting the paper nicely placed into

the guide marks on the blocks.

- didn't carve the guide marks in the correct

place.

- stretched the transfer paper when pasting it

down (if so, you'll have to re-carve that block from

scratch).

The colour is too weak. Perhaps you:

- have diluted the pigment mixture too

much.

- are not putting enough pigment on the

block.

- are not pressing firmly enough with the

baren.

Colour 'blobs' hang over the edge of the printed

areas. Perhaps you:

- are using way too much paste

- are forgetting the final gentle strokes with

the brush

Looking at this list of possible problems may make

you think that it's impossible to get it right! Actually, the

printing process is really not difficult - once you've got a bit of

experience under your belt. If your first attempt is not so

attractive, please don't give up at that point. Take a close look at

it and try to figure out what needs to be altered to improve it. If

you're still stuck after trying the hints in the above list, give me

a call and maybe I can help. If you're still stuck, then bring your

stuff over to my place, and we'll work it out together.

I hope that this little series has provided enough

of a stimulus to get you started in woodblock printmaking. I would be

very interested in seeing samples of your hand-printed pictures,

namecards, calendars, fans, book covers, gift wrapping paper, origami

paper, ex libris, stationery, and of course New Year cards. I'll make

you a promise - send me a sample of your work - and I'll send you one

of mine. I'm waiting!