The Takata children were brought up in a Japa-

nese Christian family and being Japanese they learn-

ed the same proper manners as did all well brought

up children of Japan.

"We followed strict rules," Toshi declared.

She acted out one of these rules she and other chil-

dren were obliged to follow whenever they wished to

speak to their father in another room. She dropped

to her knees by an open fusama (a sliding door in-

side a house) and carefully closed it. Then, still

kneeling, she slowly opened it. She put her hands

on the floor.

"This is the way I waited at the open door, my

head raised, waiting for my father to notice and

speak. After we finished speaking I remained kneel-

ing and reached up to slowly close the door before

standing to leave . This we did to all superiors and

our mother and father and grandparents. We were

never allowed to eat anything while stand-up. Kneel-

ing was especially necessary when addressing Father

or Mother or our grandparents before going to bed

when we came to say 'Goodnight .' "

The Takata family and families of their social

class learned two Japanese languages, a "polite"

language and an "everyday" language . Children must

use the polite language with all elders and anyone

honored. Children of a class such as a rice mer-

chant were not expected to use such polite language

and manners. Girls of families of less prestige

were known as " downtown girls" and those of Toshi ' s

class as "uptown girls."

When children of under-school age were naughty

they were usually punished by being put in υa wall

cupboard on a shelf where bedding was placed during

the day . The door was then closed . The children

were very much frightened of the dark and apologized

right away .

Toshi told of her experience. "Once when I was

put there I was not frightened; instead I went to

sleep comfortably on the piled-up bedding . Father

and Mother became worried at my being so quiet and

Mother came to open the wall cupboard. She found me

peacefully asleep and had to carry me to bed instead

of scolding me . Father laughed and said, 'Toshi is

beyond our control, but I adnire her being so fear-

less . '

"Another punishment was the most unforgetable

that ever I had. In the old days there was a ragman

who carried a big basket on his back and called out

'Kuzui! Rags to buy! Rags to buy! ' Well, one day I

was so naughty that my mother called to this ragman

and said, 'Please, Ragman, take this girl away. She

is so naughty ! ' This man being humorous said 'All

right, Ma'am' and took his bas ket from his back.

Seeing this I was really frightened and cried and

ran to Father for help . This punishment had gone

too far and ever since when I saw a raglnan I ran

away. To this day I hate to see one. I often

thought that if I ever became a mother I would never

do such a thing to a child. Mother was young then

and I suppose that I was very naughty . She may have

thought that she did the smart thing , but afterwards

my father scolded her for what she did."

Well mannered as she usually was, Toshi also

was a tomboy . As a child she moved about vigorously

and spoke out what she thought , both unusual for a

girl. Japanese education was generally intended to

train girls never to show their unhappiness, dis-

agreement or disappointment , especial

ly to men.

They were to attempt to make others happy , particu-

larly fathersr brothers, husbands and sons. Toshi's

life pattern in later years made many people happy ,

young children, older children, women, men all of

Japan, and also foreigners. This life pattern did

not come to her easily; the child Toshi had her dif-

ficulties .

Her father was wise in ways of punishing his

children for obvious wrong-doing and we see his wis-

dom in the following situation. Toshi had been

caught at some naughtiness and the elder sister car-

ried an account of it to her father. The sister

felt that Toshi's behavior had brought shame to the

Takata family as well as causing the sister "to lose

face" . The father considered the seriousness of the

naughtiness an d also the sister ' s demand that pun-

ishment of Toshi was overdue. He finally said, "We

will not punish her until she is bad naughty. "

In Japan during Toshi's childhood Christian

families and non-Christian families thought it ex-

ceedingly bad for boys and girls to be friendly .

Seven-year-olds were separated by sex and sat in

different areas . Parents and children who did not

follow this custom were condemned and called demean-

i ng names. Churches were the only meeting places

for boys and girls to meet while growing up.

Josai Takata was very independent and to a

large extent he gave his children free will. Many

boys came to visit Toshi's father who was very fond

of young people but it was Toshi's conclusion that

the boys really came to see the elder sister who was

very popular.

Toshi had little interest in fellowship with

boys; she felt them to be cheap to run after girls.

However she was not old fashioned; she used to play

with Arnerican children whose parents were American

business men and uneducated Japanese women. These

Eurasian children were free and independent and

could speak some English and some Japanese. When

she went to their homes she tasted European foo d for

the first time and when they, in turn, came to her

home they enjoyed her mother ' s Japanese food. Even

as a child Toshi liked anything unusual.

Toshi recalled years later, "So many young boys

came to our home that father was advised by his

friends to be careful of his children. He would an-

swer, ' I know my girls better than does anyone else.

If they find their own husbands the way I found my

wife, I know that they will choose the right one. '

But on the other hand he used to warn us girls re-

peatedly not to bring any disgrace on the family.

"He was very severe at times and had a bad tem-

per. He never yielded his own ideas to those of

other people when he thought that he was right and

sometimes frightened people away . But when they

w ere in trouble they used to come to my father for

help and advice.

"I was the only child who could handle him; his

other children were rather scared of him. Even my

mother when she wanted something to be done, used to

say, 'Toshi, go tell Father about it. ' I used to

scold my father for his temper and for being too se-

vere. He explained that he was spoiled by his moth-

er so much that he wouldn't like us to be spoiled. "

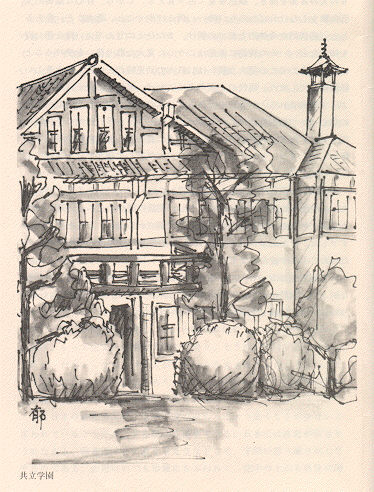

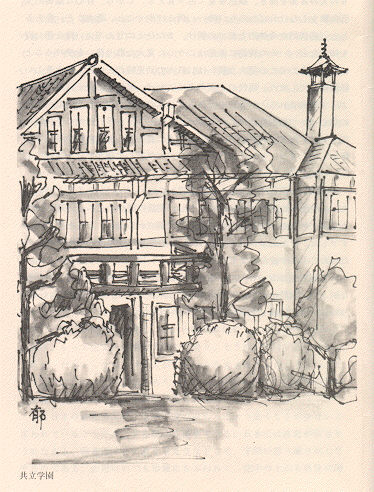

In one of Toshi's letters she wrote about her-

self at eleven years old entering her high school

life. "I came as a boarding-school student at the

age of eleven with my elder sister who was a day-

school student . We came to the first high school

for girl %s in Japan, the Kyoritsu Gakuen Mission

School founded in 1871 by the American Women's Mis-

sionary Society of New York. When in November of

1971 the school celebrated its centenial I as one of

the early graduates was there to tell of my early

days of dormitory life and episodes of pioneer mis-

sionary experiences over sixty years before.

"The school was directed by Miss Crosby who was

very strict with the girls. She made the rules and

she saw that the rules were obeyed . She dressed in

black, had white hair and moved with dignity. I

called her Miss Crow and feared her somewhat as did

the others.

"The schedule for the usual day began with ris-

ing at 5:30 followed by breakfast at sixf, cleaning

of various parts of the dorm and Morning Meditations

of twenty m yinutes.

"Meditation time was not always used for medi-

tation. Some of the girls who failed to study for

the day's work put their Bibles on their desks and

their notebooks on their laps. When they heard the

footsteps of the matron in the hall they hurriedly

closed their eyes as though to pray.

"The rest of the regular school days included

school instruction from 8:30 to 3:30. Supper was at

5:30 and vespers was followed by the evening study

until bedtime. Young girls were to be in bed by 8:

00 and older girls at 9:00.

"For the study hour about fifty girls gathered

in the big room where a woman missionary sat in the

center watching the students. The American teachers

wore long, bulky skirts and looked large like giants

to me , the youngest and the smallest. There were no

electric lights; oil lamps gave a rather dim light

but even in the dim light the students studied the

American teachers' costumes. Those costumes puzzled

all the girls. The strangest of all was that they

never changed their shoes when they came inside the

house. That I did not like."

Toshi's sister being a day-student did not ex-

perience quite all that went on. Toshi noticed a

strange noise that came from the teachers' apartment .

It was loud and recurring. She being a curious

child, and independent and adventurous , was deter-

mined to find out why . One Sunday she had a pecul-

iar illness- Sunday sick- that attacked girls when

they did not want to attend church servic es.

She explained. "When the coast was clear I

went into that place. After finding a long chain I

wondered what it could be. Then I tried to pull it

and with a big noise the water flushed down !

"And I had thought that the noise came out of

my giant teacher ! I had found the mystery. As I

thought further, this arrangement for the teachers

was unfair. There were no flush toilets for the

girls; their toilets were in back of the garden.

Inside the school building was a private one for

sick girls. Other girls had to go outdoors even in

wintertime .

"On the following Sundays after I whispered the

news, other girls had ' Sunday Sick' and experimented

with the chain . ' Sunday Sick' served other purposes ,

of course.

"Sa turdays were used for washing and big clean-

ing. The larger girls used well water for washing

and the small ones used rain water from a tank.

There was no running water. As a uniform for the

school in those days the girls all wore kimonos top-

ped with a 'hakama' that looked like a skirt.

"It was a long wait between the morning meal and

supper and the girls were very hungry, especially on

cleaning days. Often they ran to a tree behind the

school building and someone would climb to look over

the fence to a candy store , call the woman in the

store to come out and sell them candies. I as the

tomboy usually did the climbing.

"When the matron found this out she started to

give the girls boilded sweet potatoes every Saturday

after collecting two sen Efrom each girl. (There are

no more of that coin now; the least coin now is a

yen. )

"The first time of the two-sen potato feast a

bell was rung to gather the girls. Some thought the

bell ringing as a signal for a news-special and ask-

ed what the news was. Since that time the potato

was called 'Extra' . How we all enjoyed this scant

tea with sweet potato and dug right in.

The most important Saturday was the last one of

each month when there was freedom to go outside the

school grounds . Each of the girls had to take her

tiny book to the old missionary teacher. In the

book they had written in English, 'May I go to ____

and be back before dark? ' naming the place nearby .

If we made a mistake in English she would say, 'This

spelling is wrong ! Go back and write it again. ' How

disappointed we were- after dressing in a pretty ki-

mono and all ready to go- to g £o back to our rooms .

"A Iittle beyond the school there were three

hills which the girls used to call First, Second and

Third Heaven. I thought those were the names of the

hills and one Saturday I wrote in my little book,

'May I go to heaven? I will be back before dark. '

I took it to Miss Crosby. She did not understand at

all what I meant and said, 'Toshi, if you went to

Heaven you could not come back before dark. ' But I

insisted on going and when I came back I went to

Miss Crosby to get back my book. In the meantime she

had found out what I meant for heaven. She asked me

if I had a good time in heaven, so I said that I had

a wonderful time.

"Then she held both my hands and kissed me ten-

derly and said, ' Toshi, some day you will have to go

to Heaven. This Heaven would be a more beautiful

and a much happier one than you saw today . For that,

you must be a good girl and must love Jesus. Do you

understand?' Ever since that moment I was never

afraid of Miss Crosby and we became good friends.

This was the first kiss I ever had. Japanese in

those days never showed affection by a kiss, even in

families .

"Dormitory life became somber during examina-

tion time. The bigger girls wanted to get up early

to study. The building was cold so they wrapped

themselves in blankets and went to the dining room

to study under the light of oil lamps while the

maids were getting breakfast. Some of the larger

girls asked me to call them at 4:30 or 5:00 in the

morning thus using me as a kind of alarm clock. I

mwas the youngest and the smallest and I went around

the dorm from the far end of the west wing and then

to the south wing to wake them up in the cold and

the dark. They said, 'I will help you with the vo-

cabularies ' and sometimes they also helped me with

the translations so that I did not have the trouble

to use the dictionary."

And so passed seven years for Toshi in the Kyo-

ritsu Gakuen Mission School in the early 1900's. At

the age of 79 Toshi was the high light of that

school's centenary program. She was a living con-

tinuation of herself of those early High School days

as she developed her charm. A Ietter of November 6 ,

1971 included here gives some understanding of her

life at her advanced age.

@@@@@@@ @November 6, 1971

Dearest Elsie.

Your long and interesting letter came

yesterday. It pleas σed me very much to

know that you still are anxious to write

my story . I thought you have given up !

I 'd been very busy with the new class-

room project. Finally I could manage to

borrow from the government enough money

with ten years lease. The room was com-

pleted and we are using it. No end of the

story to tell you how I could manage this !

Last week we had the centenary anni-

versary of the school where I had been

brought up in my early days. I was put on

the program for four days plus many extra

speeches. This made me very busy and

tired, but I am quite well now. So you

see how my days have gone by.

On the program of the anniversary the

students gave the pageant of the hundred

years history of the school, and in be-

tween I gave the speech of old times of

missionaries and dormitory life. I was

told by many , many people that the high-

light of the program was my speech. So

many hearing of the old times had more

than seeing the pictur ϊs, even, felt some-

thing real and present of the early folk.

I received many appreciation letters, too .

So while the iron is hot I'll try to

record it and send it on to you as a test

and if you find it all right I'll send

some more. I have a tape recorder but I 'm

using "cassetts" which I find easier to

handle. Perhaps you have one , too, or

maybe David has one . It is very popular

among students here.

If you were in California I certainly

would come to see you and we could talk

and talk. Now Bloomington seems too far

away .

What a strange life this is! I know

my time is getting very short .

Please give my love to Dorothy and

the Crawfords and much, much love to your-

self .

@@@@@@@@@@@@@ In haste,

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@Toshi

The outbreak of World War I forced both Japan

and the United States to look beyond their shores

and they exchanged i φnformation intended to lead to

further understanding. It was at this time that a

diminutive Toshi Takata , now grown to womanhood,

sought her first employment . She faced her future

in a culture which had not welcomed women into pub-

lic life. How could she profit from her years of

education in both English and Japanese ? Could she

become financially independent ?

Traditionally women of Japan had been prepared

for two roles, that of a wife and mother or that of

an entertainer with highly prized social graces.

Traditionally Japanese men had rejected women who

sought positions of political or business influence.

It is reported that for centuries Japanese wom-

en have been oppressed by their menfolk. Japanese

men in general were given something of the status of

the lower gods while Japanese women were expected to

serve and with few rights. The women through the

centuries might not like the system but they had to

put up with whatever female and male behav yior was

considered proper by only the men themselves.

This had not always been true. Before 769 A.D.

Japan had been ruled by seven empresses. An emper-

or's widow, Jingu, in the third century A.D. @led the

military forces that conquered Korea. Ancient Japa-

nese literature often referred to powerful priest-

esses and until the 14th Century the high priest of

Ise, the most holy of the Shinto shrines, was one of

the emperor's daughters. In the historic times sev-

eral sons took their mother's name . Many women were

poets and the most famous literary work, Tales of

Geni, was written by a woman.

It was during the Sixth Century that the posi-

tion of Japanese women gradually worsened ; Chinese

civilization began its influence on the island na-

tion and by the Thirteenth Century Japanese women

had become perpetual slaves first for fathers, then

husbands and then oldest sons. Buddhism as well as

Confucianism reduced oriental women to practically

total subordination .

However, various and lone Japanese women grew

up in unexpected survival . Some became known for

their independent thinking and their independent if

sporadic actions. Toshi Takata had childhood dreams

of teaching, of visiting America and of knowing for-

eigners. By the time she became an adult these

dreams became firm purposes. They led her into dif-

ficulties that few women in Japan had ways of over-

coming during the early 1900's.

The men of the Takata family regarded Toshi

differently.

Her father often said, "Toshi should

have been a boy"- the strongest of Japanese compli-

ments. He supported her as a woman in her ambitious

undertakings as he had in her childhood vagaries.

He had misgivings at times and was an anxious parent

but in the end he grew immensely proud of her.

Somehow her energy plus her intelligence plus

her Christian values plus her happy Japanese upbring-

ing urged her on. There is a familiar saying that

Japanese babies do not cry or cry less than most ba-

bies in other parts of the world. The explanation

is simple. When Japanese babies show signs of cry-

ing the mothers give them whatever they want, usu-

ally something to eat . Babies also had rides all

day on the backs of their mothers and they look ove r

the shoulders taking in the situations through words

and facial expressions of the people near by. Japa-

nease babies get this generous treatment at the time

of life when they are learning the most basic accom-

plishments- walking , talking , thinking and bodily

and emotional controls with the ultimate understand-

ing of when and when not to impose oneself on oth-

ers. Generous treatment makes Japanese babyhood a

joyous experience .

Modern psychologists agree that learning is re-

inforced by pleasure . Could this be the reason why

Japanese are eager learners as well as hard workers

all of their lives ? Japanese children are suddenly

expected to "grow up" at about four or five years of

age and this ends their life of joyous babyhood but

does that joyousness reinforce the learning process

with enough impetus to make learning satisfying dur-

ing a whole lifetime?

T Οoshi Takata's first position in the public

world was with the JAPAN TIMES. The work was inter-

esting to her and gave her valuable experience in

improving her English. She typed in English all the

various news articles before they were sent to the

printer of the newspaper. She also translated art-

icles from the Japanese.

This first position proved to be encouraging.

No one rejected her because she was a woman, or a

Christian in a non-Christian society, or of an in-

dependent mind in a culture when women were not ex-

pected to be independent. The world was getting

smaller and the United States and Japan desired more

exchange of news .